Dark Star: Lost (and Forgotten) in Space

Cinematic Semicentennial Series – 1974 Edition

Before Halloween, before The Fog, and before The Thing, there was Dark Star. John Carpenter’s directorial debut is a curious and quirky foray into low-budget science fiction cinema. Let’s chart a course for the Veil Nebula and venture right into Carpenter’s space flick.

The film’s title screen

The Mission

It is the 22nd century and the crew of interstellar cruiser Dark Star are traveling the far reaches of the universe to locate and destroy unstable planets in advance of colonization efforts in space. And just how does one destroy a planet? You detonate an exponential thermostellar “smart bomb” of course. These bombs are very smart indeed, each informed by a form of artificial intelligence, a clear sense of its purpose, and a bit of personality. This fact will come into play later.

Twenty years into their mission, the Dark Star’s four-man crew is burnt out, bored, and homesick. Yes, a solitary mission blowing up planets can become tedious after a while: locate, bomb, repeat. Not helping matters are the ship’s tight, cramped quarters (as someone prone to claustrophobia, I could not imagine myself cooped up in this ship for 20 minutes let alone 20 years.) The craft is also showing her age as its systems often break down and are in regular need of repair. And to add insult to injury, the ship’s entire remaining supply of toilet paper has been destroyed. THAT is where I draw the line!

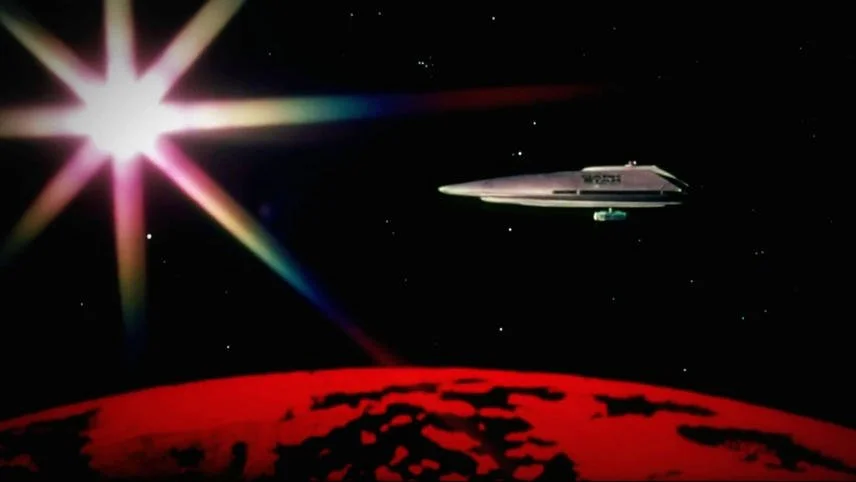

The Dark Star

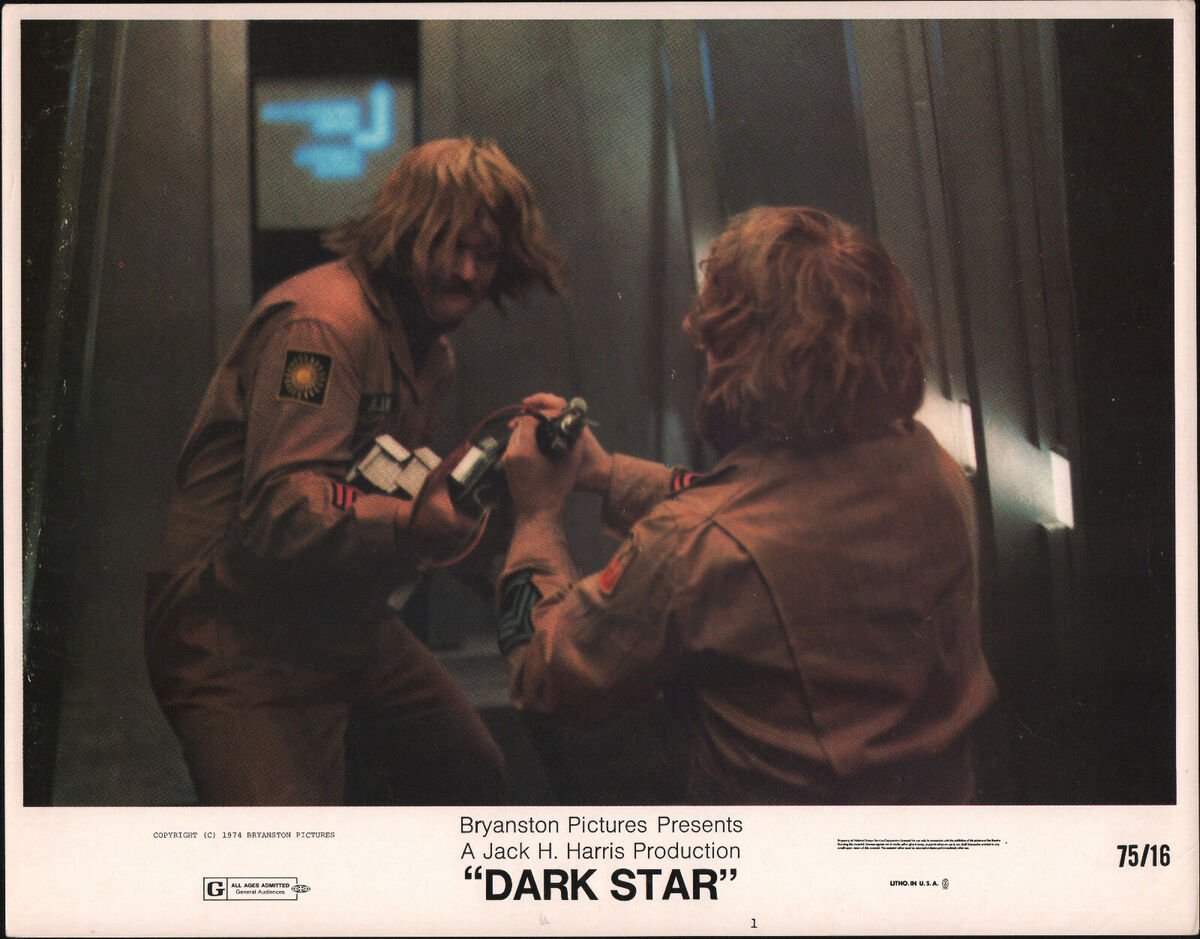

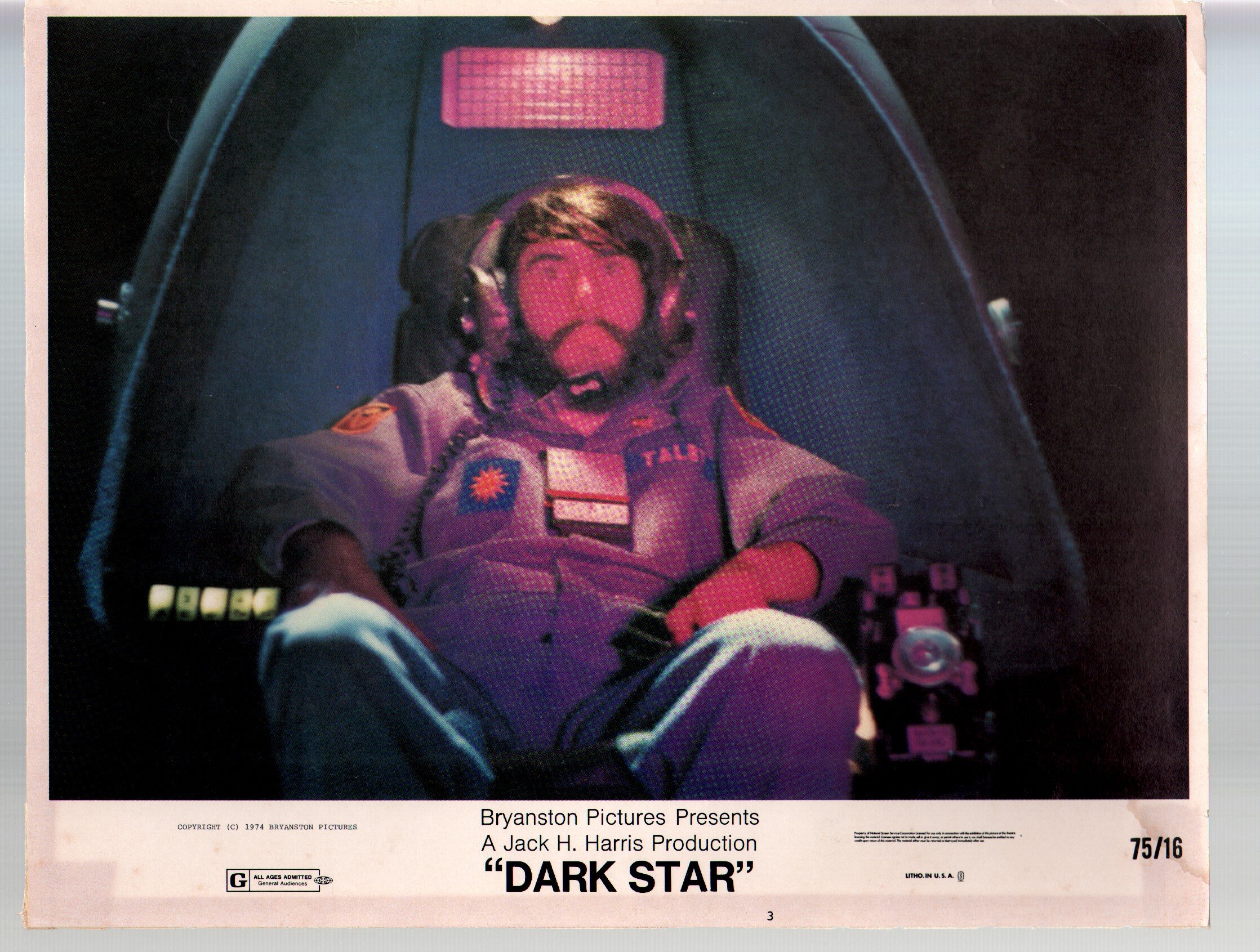

Meet the spaced (and bummed) out astronauts of the Dark Star

Our depressed crew includes Pinback (Dan O’Bannon), Talby (Dre Pahich), Lt. Doolittle (Brian Narelle), and Boiler (Cal Kuniholm). When not seeking out and destroying planets, they pass the time playing cards, reading magazines, and listening to lounge music selections chosen by the ship’s computer. Morale is low to say the least as the team languishes in isolation and with a sense of being forgotten in cold, deep space. And while the crew receives periodic video transmissions from earth that are meant to boost morale, they only come across as perfunctory and patronizing.

Pinback is extremely frustrated by his crew mates who spurn his attempts to lighten the mood or improve morale on the ship, while Doolittle resents his defaulting into a leadership role and pines for his surfing days in California. Boiler, seemingly indifferent, bides his time playing games with his favorite knife and trimming his mutton chops. Talby mostly keeps to himself, preferring to spend time in the ship’s transparent dome, gazing at the stars and planets, and hoping to catch a glimpse of the mysterious Phoenix Asteroids. And though the events of Dark Star are meant to take place in the mid-22nd century, an abundance of long shaggy hair and thick beards clearly signals that the film was made in the early 1970s.

The fifth member of the crew is Commander Powell, who died before the events of the film. However, the commander is stored in a cryogenic freezer compartment and is available for consultation. Somehow, 22nd-century technology will allow us to communicate with the dead.

The Socratic Method in Space

To make matters worse, a meteor storm has damaged the ship’s computer system, compromising its failsafe measures and prompting Bomb #20—a clear nod to 2001’s HAL 9000—to attempt a detonation. It is now up to Doolittle to talk #20 out of blasting them all to oblivion. At the suggestion of Commander Powell, Doolittle actually attempts to teach Bomb #20 phenomenology (essentially, the understanding of our subjective experience) in the hope that reason will win the day. The two have a brief philosophical debate about existence and reality, as the seconds count down to detonation. This is a very fun scene and a comedic take on themes tackled in more sobering sci-fi films of the era, wherein humanity is forced to grapple with an artificial intelligence that is growing beyond its power and control. Movies in this vein include the previously mentioned 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Collossus: The Forbin Project (1970), and Westworld (1973).

I would be remiss if I did not mention that there is also a mischievous alien on board. I want to remind us here that Dark Star has its origins as a student film (lest anyone expect a fascinating, elaborate creature design). In this minimalist production, the alien is an actual beach ball that has been painted with red spots and given clawed feet. The Dark Star creative team clearly leaned into the comedy angle here, most likely recognizing that they did not have the time or budget to create an elegant or fearsome alien design.

Dark Star gets caught in a meteor storm, while Bomb #20 is ready for duty.

Student Film

While I often suggest approaching a new film as cold as possible, in this instance a bit of background and context may be in order.

Dark Star began as a school project of film students at the University of Southern California (USC) in the early 1970s, led by John Carpenter and Dan O’Bannon. Both would go on to make their mark on horror and science fiction cinema of the 1970s and 1980s, Carpenter predominantly as a director with a knack for creating memorable scores for his films and O’Bannon as a screen writer with some special effects acumen. Joined by a cast and crew of fellow USC students, Carpenter and O’Bannon would drive the production of Dark Star for more than two years, making progress in fits and starts as time and budget would allow. Carpenter directed the film, co-wrote the script, and composed the score while O’Bannon co-wrote and edited the script, supervised special effects, and functioned as a production designer. O’Bannon also played Sergeant Pinback.

If you are interested in learning more about the production history of this scrappy oddball sci-fi romp, I would recommend Let There Be Light: The Odyssey of Dark Star (link in the supplements). It was interesting to learn how the film grew from a 20-minute black-and-white short, to a 50-minute color film, to a full-length feature. The documentary details the sometimes wonky and intriguing production history, with commentary from its many contributors.

My two cents

Dark Stark is an offbeat and absurdist riff on 2001: A Space Odyssey. Its often comedic tone and dark, grungy aesthetic stand in stark contrast to the far more serious 2001 with its reverence for its subject and its elegant and expansive visuals. While the pace is clunky and plot is sparse, there are things to like about Dark Star.

When you consider its student film origins and extremely low budget that had to be cobbled together over a couple of years, I can’t help but feel endeared to Dark Star’s rudimentary, can-do set design constructed with whatever the creators could get their hands on at the USC campus or at the local 99 cents store. For instance, the computer panels in the control room feature white, backlit ice cube trays, while Talby’s star suit was constructed with various random household items, including a chest panel made from a muffin tin flipped upside down. Kerosene mist was used for a scene where Lt. Doolittle consults with Powell in the cryogenic compartment. Also take note of the hyperdrive sequences, featuring low budget yet effective visual effects that might remind one of the light speed sequences in Star Wars.

As mentioned earlier, this film has an extremely threadbare plot, and a sizable portion of the run time is dedicated to our crew’s efforts to pass the time between planet bombing assignments; this may frustrate fans of tight, fast-paced story telling. There is an extended sequence that was added to the film to ensure that the runtime reach that of a full-length feature. I leave it to the viewer to figure out which was the added sequence, but will say that it is more entertaining than many other commonly used methods used to pad a runtime, such as extended shots of people walking and/or driving, a common filler technique employed in B-movies of earlier decades.

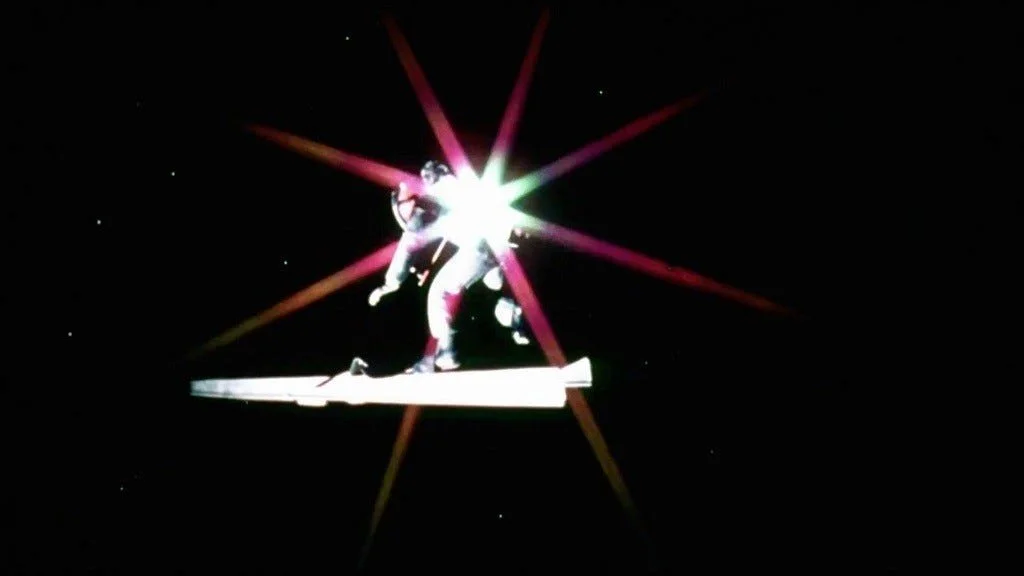

Surfing amongst the stars

While none of the cast will be mistaken for Daniel Day Lewis, the performances by these inexperienced actors and students portraying a forlorn and bumbling crew on a dilapidated ship in the far reaches of space somehow works.

There are a few moments at the end of the film that strike me as surprisingly poignant especially in an otherwise nihilistic and parody-driven movie. As Talby and Doolittle embrace their fates and place in the cosmos, they also affirm their mutual respect and affection for one another. I thought this was a wonderful way to end the film. As we enter the new year may we all approach the unknown with such kindness, curiosity, and grace.

The music for Dark Star was provided by Carpenter, who wrote and performed the electronic score using a modular synthesizer. Fans of his films will catch hints of his later scores for Halloween, among others. The tone of many a Carpenter film is set the very moment that synth-heavy score kicks in over the opening credits. Carpenter often collaborated with composer and sound designer Alan Howarth to create many iconic scores for films such as Escape from New York (1981), Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982), Christine (1983), Big Trouble in Little China (1986), Prince of Darkness (1987), and They Live (1988).

Dark Star also features a catchy theme song, “Benson Arizona,” which plays over the opening credits and remerges at the end of the film. Somehow this easy sounding country ditty, written specifically for this film, really works. The music was written by Carpenter, with lyrics by Bill Taylor. The lead vocals were provided by John Yager, a friend of Carpenter’s from USC.

I would recommend Dark Star to aspiring John Carpenter completists who may have seen films such as Halloween, The Thing, and Christine, but haven’t caught this obscure earliest selection from his filmography. I have no doubt that some viewers may struggle to embrace Dark Star’s nihilism juxtaposed against some goofball comedy. Still, this movie is a true curiosity that should not be dismissed outright.

Dark Star at 50

Dark Star premiered at Filmex, the Los Angeles International Film Exposition in the early spring of 1974, followed by a limited theatrical release in 1975. Producer Jack Harris, best known for producing The Blob (1958), helped promote the film and convinced the filmmakers to shoot an additional 15 minutes of footage to round out the film to feature length. While the movie was not a box office success, Dark Star drew some enthusiastic attention at midnight screenings and on college campuses. Subsequent home video releases on VHS, DVD, and Blu-ray, plus some renewed critical attention on its 50th anniversary ensured that this star has not completely died out.

George Lucas took note of Dan O’Bannon’s computer animation work for Dark Star and later hired him to do some similar work on Star Wars. O’Bannon also wrote, with Ronald Shusett, the original story and the subsequent screenplay for Alien (1979), a towering achievement in classic sci-fi/horror cinema. Over the next couple of decades O’Bannon’s screenplays and original stories contributed to many efforts in science fiction and horror, including Dead and Buried (1982), Lifeforce (1985), Invaders from Mars (1986), Total Recall (1990), and Screamers (1995). O’Bannon also wrote and directed The Return of the Living Dead (1985), a horror comedy that has major cult following. He died of complications from Crohn’s disease in 2009. To read more about his somewhat underappreciated contributions to the sci-fi and horror genres, check out the Collider piece in the supplements.

John Carpenter would follow up this debut effort with 1976’s Assault on Precinct 13, an action crime thriller and siege film about a Los Angeles gang targeting a nearly shuttered police precinct. Carpenter describes it as part Rio Bravo, part Night of the Living Dead. It’s one of my favorites of his filmography and I can’t wait to talk about it in the future. Peak Carpenter for me is the series of revered horror and science fiction films he directed from the mid 1970s through the late 1980s, many of which I have already mentioned. He continued to direct films through the 1990s and 2000s that I feel are a lot more hit or miss. Carpenter seems to have largely folded up his director’s chair and now spends his time performing his iconic film scores live, playing video games, and serving (however reluctantly) as the elder statesman of horror and science fiction cinema.

There is so much more to cover relevant to Carpenter and O’Bannon but in the interest of time and space, I’ll think we’ll save those for future discussions. Afterall, this site is dedicated in large part to sci-fi and horror cinema so it’s an extremely safe bet that we’ll be circling back to them often.

Dan O’Bannon and John Carpenter (foreground) on the set of Dark Star

Did you know?

Nick Castle, who worked as a camera operator on Dark Star, would go on to play Michael Myers, a.k.a “The Shape” in Halloween (1978).

The budget for Dark Star was approximately $60,000.

Director John Carpenter has referred to Dark Star as “Waiting For Godot in space.”

Plot fun fact: the character of Pinback is actually a fuel engineer that ended up on the Dark Star through a case of mistaken identity. His real name is Bill Frugge. Pinback is the astronaut whose place he inadvertently took. Oooops!

How did I watch?

Streaming on Peacock

Cast (abridged)

Dan O’Bannon – Sgt. Pinback

Dre Pahich – Talby

Brian Narelle – Lt. Doolittle

Cal Kuniholm – Boiler

Cookie Knapp – Computer

Crew (abridged)

Original Story and screenplay – John Carpenter & Dan O’Bannon

Production Design & Special Effects Supervisor – Dan O’Bannon

Produced & Directed – John Carpenter

Music – John Carpenter

Cinematographer – Douglas Knapp

Production Companies – Jack H, Harris Enterprises, University of Southern California

Distributor – Bryanston Pictures

Recommendations based on Dark Star-

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Collusus: The Forbin Project (1970)

Halloween (1978)

Alien (1979)

Starman (1984)

The Return of the Living Dead (1985)

Invaders from Mars (1986)

Running Time: 1h 15m

Rating: G

Supplemental Recommendations-

Let There Be Light – The Odyssey of Dark Star (documentary available on YouTube)

Dark Star at 50: How a micro-budget student film changed sci-fi forever (BBC)

This Guy Doesn’t Get Enough Credit as a Horror and Sci-Fi Master (Collider)