Blood is the Thing: Ganja & Hess (1973)

opening title of Ganja & Hess.

Fresh off of Black History Month, we decided to feature a Blaxploitation-era art house horror film that does not quite fit neatly into this sub-genre. This is a film that I only recently came around to watching, and man does it offer some food for thought. Ambiguous and hazy in many ways, Ganja & Hess is cerebral, ghastly, moving, and altogether strange. You can pull on so many threads in this film, and many critics have. For now, let’s start with the exposition and take it from the top.

In the Beginning . . .

Leading into our opening credits is a very cursory, cliff notes-style synopsis:

Doctor Hess Green

Doctor of Anthropology

Doctor of Geology

While Studying the Ancient Black Civilization of Myrthia

was stabbed by a stranger three times…

One for God the Father

One for the Son..

And one for the Holy Ghost…

Stabbed with a dagger,

Diseased from that ancient culture…

Whereupon he became addicted

And could not die…

Nor could he be killed

We transition to a church where Rev. Luther Williams (Sam L. Waymon) delivers a lively, joyous sermon to his all-Black congregation. His own voiceover narration tells us how preaching brings him so much joy and comfort. He also explains that he makes extra money as a chauffeur for Dr. Hess Green, an addict (not a “criminal”), whose addiction is to blood.

Dr. Hess Green

Hess

Hess Green (Duane Jones), a scholar of anthropology and geology, lives in a lavish if slightly bohemian-style mansion in the Hudson Valley, a bit north of New York City and within view of the Hudson River. He is wealthy, erudite, multilingual, smartly dressed, and a bit reserved. He holds garden parties on his bucolic estate, retains a private tutor for his son, is chauffeured around in a Rolls Royce, and generally exists in a position of wealth and status in an otherwise all-White community. He is waited on hand and foot by his devoted butler Archie (Leonard Jackson).

As our opening text explains, Dr. Green is studying the (fictional) ancient and long-died out African culture of Myrthia, which practiced the drinking of human blood. Dr. Green hires a new research assistant, George Meda, played by the film’s screenwriter and director Bill Gunn. Meda, as he prefers to be called, comes to stay at the Green estate as he settles into his assignment. It soon becomes clear that Meda is psychologically unstable. In one telling scene he sits down with Hess for post-dinner drinks and conversation and right away the viewer can tell that something is off. Meda shares strange non sequiturs and awkward anecdotes, and he exhibits a palpable tension that’s lurking just under the surface.

Our first of several dream sequences occurs later that night when Hess falls asleep holding a Myrthian dagger. Sure enough, he dreams of the Myrthian queen. She strides among the tall grass donning a striking headpiece sprouting long bird feathers; she is trailed by her dutiful male retinue. They are accompanied by the sound of girls singing a “Bongili Work Song” (going forward I’ll refer to this as the Myrthian theme). Both the image of the queen and the theme will be revisited several times in this film.

The Myrthian Queen of Hess’s dreams.

In the middle of the night Hess finds Meda sitting in a tree, a noose hanging off a nearby branch. He is drunk, paranoid, erratic, and belligerent. Hess is as calm and as gentlemanly as he can be as he tries to talk his guest down. Meda subsequently admits that he has a history of suicidal ideation. Later that night as Hess is half asleep in his bed, Meda attacks him with an ax. The two engage in a brief struggle that ends with Meda stabbing Hess with the ceremonial Myrthian dagger. Following this attack, Meda engages in a series of bizarre behaviors and ultimately shoots himself in the chest. Hess emerges with no wounds to show for his stabbing; he is momentarily shocked then drops to the ground to slurp up Meda’s blood as it pools on the bathroom floor. The Myrthian curse has clearly taken its hold of Hess.

At first, Hess attempts to satisfy his new addiction by stealing blood packs from a doctor’s office; this does not last long as he soon recognizes the need to consume fresh blood. He visits a club of disrepute to meet a prostitute who is to be the source of his next fix. Unluckily for Hess, the woman’s pimp intercedes and a fight ensues where Hess is stabbed and shot to no effect. In a fairly graphic scene, Hess kills the two then opens their arteries with a razor, and we are left to watch the blood rhythmically drain from their bodies. We again hear the Myrthian theme accompanied by an unsettling buzzing sound. Hess looks on at the bodies, shocked and bewildered in the aftermath of his first murder.

From here on, we see Hess targeting other victims, often via disturbing and cruel attacks. He stores their blood to consume later on, and when the craving becomes unbearable he dips into his stores and sips them nonchalantly from a glass. By now it is obvious that we are not in for a traditional vampire film in the mold of Bela Lugosi or Christopher Lee. No hypnotic stares, no black capes, and no dramatic baring of sharp fangs sinking into the necks of (mostly) female victims. Hess is something else.

Ganja

Meda’s wife Ganja (Marlene Clark) soon enters the picture. She calls Hess from the airport having just flown in from Amsterdam looking for her husband. Low on funds, she asks if she can stay with him for a few days. Ganja initially comes off as crude, pushy, angry, and fed up with Meda and his mental health issues, but we see her demeanor ebb and flow throughout her stay with Hess. Soon after Ganja settles in, she and Hess take up with one another and consummate their new relationship. Ganja continues to be a chameleon-like figure: she can be elegant and gracious at one moment, then brazen and demanding at another. Hess, meanwhile, continues to dip in and out of the attic where blood is stored in order to quell the pangs of his addiction.

In a twisted turn of events, Ganja accidentally stumbles upon Meda’s frozen body while looking for wine in the cellar. Although briefly upset and disturbed, she seems to shake off this reality rather quickly and picks up where she and Hess left off. Although we don’t know a lot about Ganja, we do learn via an extended monologue that she grew up with an unloving mother and suffered a troubled childhood. This clearly informs how Ganja lives her life: with a determined approach to self-preservation.

Ganja & Hess – bonded by blood

In many ways Ganja and Hess are like any other couple—they have heart-to-heart conversations, are playful and goofy with one another, and share moments of pure love and affection. The two are married on a sunny summer day with Rev. Williams officiating and a few witnesses looking on. The Myrthian Queen appears in the background, suggesting that this legacy of blood and addiction is ever present. On their wedding night, Hess tells Ganja, “you know I want I want you to live forever?” Well, I am sure you can see where this is going. Will this legacy of addiction continue indefinitely? I don’t want to give away any more but will only say that the latter half of this film will be bathed in blood, religious fervor, sex, murder, phantasmagoric imagery—and some cathartic moments.

My two cents

Though released in the middle of the Blaxploitation era, Ganja & Hess eschews many of the stylistic choices of its contemporaries. This is an avant-garde horror film to be sure and one that features a predominantly Black cast and creative team, which was atypical up to that point. While its unconventional and nebulous narrative may not resonate with some viewers, this film is indisputably original and an important addition to the history of Black cinema.

According to various sources, Philadelphia-born writer/director Bill Gunn was approached by producers Kelly-Jordan Enterprises, Inc. to make a Black vampire film in a similar vein (no pun intended) to 1972’s Blacula, which was a major hit. Gunn, however, ended up shooting a film that was anything but traditional or formulaic. Ostensibly still making a vampire film, Gunn was more interested in exploring the subject of addiction, among other things.

Gunn was a novelist, playwright, screenwriter, and actor for stage and television. He is considered a pioneer in Black filmmaking becoming only the second Black film director for a major studio (Warner Bros). In 1970 he wrote, cast, co-produced, and directed Stop, a film about an unhappy couple moving to Puerto Rico to rekindle their marriage. It was considered highly controversial, drawing an X rating and was subsequently shelved and never released.

Gunn also wrote the screenplay for Muhammad Ali’s biopic, The Greatest (1977), though he was ultimately uncredited in the final version of the film. He also directed the all-Black experimental and quasi-improvisational ensemble drama Personal Problems (1980). He wrote a series of plays and several musicals including Black Picture Show, Rhinestone, Family Employment, and The Forbidden City. Sadly, Gunn died young at the age of 54.

Bill Gunn on the set of Stop

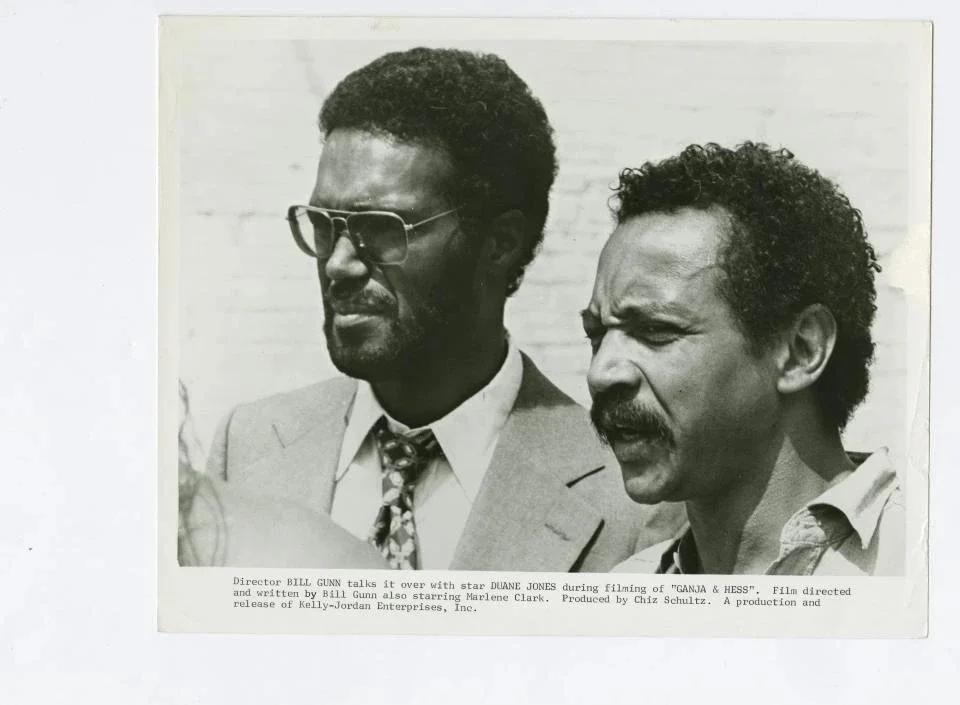

Director Bill Gunn and actor Duane Jones on the set of Gangja & Hess. Photo courtesy of Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture/NYPL, Photographs and Prints Division

Gunn’s film delves into many themes relevant to race, Christian and pre-Christian spiritual traditions, sexuality, class, and gender, and portrays blood as the thread connecting trauma across generations and civilizations. To take a deeper dive into these themes and learn more about the production, I recommend reading the excellent BBC piece linked in the supplements, which celebrates the sometimes-misunderstood film in the wake of its 50-year anniversary. It also gets into the fraught and misguided attempts to market and rework the film in the U.S. after its positive reception at the 1973 Cannes Film Festival's Critics Week.

While I wouldn’t go as far as to say that Ganja & Hess is inscrutable or that it defies description, I will say it is a very unique and puzzling film that offers many avenues for interpretation. Gunn forgoes a crisp, clear narrative and tight pacing for a more hazy, dreamy, and unhurried style of storytelling. The camera lingers on characters (primarily Ganja and Hess) as they share long moments of quiet punctuated by bits of dialogue. It’s as if the two are taking each other in, sizing each other up, or perhaps a bit of both. Although this is inarguably a horror film, the pacing of it is leisurely, which seems to mirror the pace of those hot, balmy mid-Atlantic summers we on the East Coast know so well. There are also several striking slow-motion sequences of our characters running around the hills and fields of the Hess estate, evoking sadness, fear, and even joy.

The small but mighty cast is fantastic. Bill Gunn plays the unhinged George Meda almost too realistically; his portrayal of this minor yet pivotal character is unnerving. Fans of zombie films are very familiar with Duane Jones, who played Ben in the game-changing horror classic Night of the Living (1968). Jones made less than ten films in his career, opting to spend more time in academia as an administrator and acting teacher. He delivers a memorable performance as the sophisticated, cursed, and love-struck Hess Green, who can be weary, sympathetic, and at times menacing. I would love to have seen him in more genre films. Alas, like Bill Gunn he was taken too soon at the young age of 51.

A note about sound: some viewers may struggle to hear the actors’ lines clearly. I am unsure if this is due to the quality of the original audio recording or the actors’ performances. Either way, I suggest watching this film with the volume turned up and subtitles turned on.

Marlene Clark holds her own as Ganja Meda. While she comes across as pushy, crass, and calculating early on, she slowly reveals that there is a lot more to her story. One can argue that Ganja represents a version of an empowered Black woman that runs counter to the Black female characters seen in many Blaxploitation films of the time. Check out the fascinating Fangoria magazine piece linked in the supplements that delves into this notion—it certainly got me thinking. Lastly, composer Sam L. Waymon does double duty by playing the gentle, soft-spoken Rev. Luther Williams, who is downright ebullient when preaching. Leonard Jackson is also great as the precise, proper, and deferential Archie.

Behind the gauzy and sometimes grainy images is a beautiful-looking film. Much of the the on-location shooting took place at Apple Bee Farms in the Hudson River Valley town of Croton-on-Hudson. Cinematographer James E. Hinton took full advantage of the Hudson valley settings, lingering on shots of its lush and rolling green hills, tall prairie grass, and clusters of trees with dappled sunlight peaking through. The interior of the Hess mansion is also rich with detail: fine art, pottery, books, African and Western art, tables, antiques from antiquity, books, and candlelight all suggest a life of study, exploration, and privilege.

The music for Ganja & Hess, composed and performed (in large part) by Sam Waymon is quite eclectic. It includes a bit of rock, equatorial African songs, church gospel, and electronic music. The Mrythian theme accompanies every scene that involves murder, bloodletting, and drinking. Layered on top of that is an unrelenting and unsettling buzzing sound that creates a very uneasy feeling. There are also several extended sequences involving Rev. Williams’ church choirs singing and dancing that are exuberant and offer a tonic to some of the macabre and perverse proceedings. There are two songs that stand out in this film. The first is the film’s opening song, “Blood of the Thing,” which evokes an African American spiritual and touches on some of the themes of ancestral trauma discussed earlier. The second “You Got To Learn, To Let It Go” is featured throughout the film and in several variations.

Something I would have liked to have seen more of is the history of the fictional civilization of Myrthia. I kept wondering: how did they come into this blood curse? My own curiosity aside, I know this is not necessarily the type of film to be asking such questions. Gunn and the creative team seem to have been much more focused on introducing ideas and suggested themes through dreamlike imagery and nebulous mode—this isn’t a movie for those seeking concrete answers and a straightforward story.

I would be remiss if I didn’t include this disclaimer: the film features a good bit of nudity, sex, and blood, sometimes all three at the same time. And while artfully depicted and not overly explicit by today’s standards (have you seen Poor Things?), it still bears mentioning.

Did you know?

Marlene Clark also appeared in Bill Gunn’s directorial debut Stop (1970).

The scenes in Rev. Williams’ church were shot across the Hudson River from Croton-on Hudson in an actual church in Nyack, New York. I believe the church is still there and I am eager to find it the next time I visit.

Gunn eventually moved to Nyack and was living there when he passed away in 1989.

In 2024 Ganja & Hess was one of 25 films named to the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry for Preservation. These films were selected due to their cultural, historic, or aesthetic importance to preserve the nation’s film heritage.

Some scenes were shot at the Brooklyn Museum.

The Spike Lee-directed film Da Sweet Blood of Jesus (2014) is a remake of Ganja & Hess.

The film’s budget was approximately $350,000.

Composer Sam Waymon is the brother of the legendary singer and civil rights activist Nina Simone.

Artwork celebrating the restoration of Ganja & Hess by The Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) and The Film Foundation.

How did I watch?

Blu ray Kino Lorber

Cast (abridged)

Duane Jones – Dr. Hess Green

Marlene Clark – Ganja Meda

Bill Gunn – George Meda

Sam L. Waymon – Rev Luther Williams

Leonard Jackson – Archie

Mabel King – Queen of Myrthia

Crew (abridged)

Director – Bill Gunn

Writer - Bill Gunn

Composer – Sam L. Waymon

Cinematographer – James E. Hinton

Production Designer – Tom H. John

Costume Designer – Scott Barrie

Producer – Kelly-Jordan Enterprises, Inc.

Running Time: 1h 52m

Recommendations Based on Ganja & Hess-

Let’s Scare Jessica to Death (1971)

Blacula (1972)

Messiah of Evil (1973)

Daughters of the Dust (1991)

Candyman (1992)

Supplements

Ganja & Hess: The 50-year-old vampire movie masterpiece critics got all wrong (BBC)

Blood And Money: GANJA & HESS. Marlene Clark serves up subversive Black Feminism. (Fangoria *Note that this article contains significant spoilers

Sam Waymon and his Partnership with Bill Gunn (Screen Slate)

Next Up - We begin our Women’s History Month series featuring four horror films directed by women.