Surveilling The Conversation

Cinematic Semicentennial Series – 1974 Edition

These days, it’s hard to imagine a world where our privacy is sacred; that is, a world where our personal information and daily movements are untracked and unharvested by large predatory corporations to further their own bottom line. As we continue to surrender our sense of privacy and become further immersed in the world of AI, I wanted to look back at the almost “quaint” days of audio surveillance via 1974’s The Conversation, a quiet and understated piece where intrigue and paranoia collide and technology threatens to upend lives.

Our film’s opening credits roll as we are treated to an overhead shot of San Francisco’s Union Square on an early December day. The park is bustling as people stroll, chat, and have lunch; buskers ply their trade and one particularly enthusiastic mime works the crowd. Our attention eventually turns to a young, slightly nervous-looking couple engaged in the titular conversation as they meander through the square.

The conversation.

Listening in

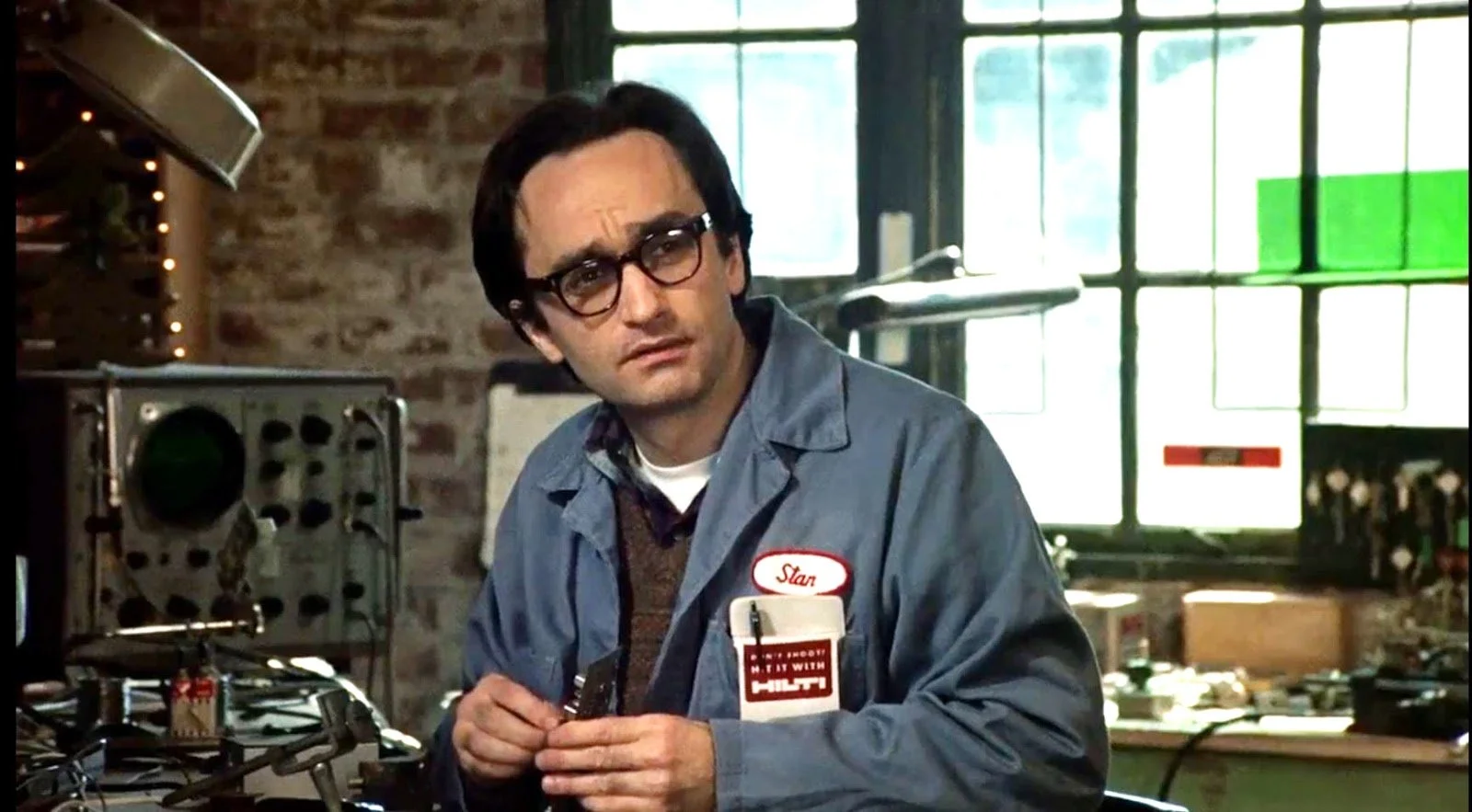

This conversation is of great interest to one Harry Caul (Gene Hackman), an expert in private surveillance. Harry and his assistant Stan—played by the late, great, and gone way too soon John Cazale—are working to record the couple’s every single word for a private client. Harry, Stan, and a small team of buggers manage to capture the conversation via three separate recordings; this is done with the help of careful planning, technologic ingenuity, and meticulous post-recording work.

It becomes clear that Harry is a man of great audio surveillance talent who is preceded by his reputation for being one of the best wire tappers in the business. The full conversation, initially captured in small snippets, is synchronized and spliced together into a set of tapes that Harry is to turn over to his client, along with supplemental photos.

He arrives at the corporate office of a bigwig executive referred to only as “the director” (Robert Duvall). Harry soon becomes trepidatious when he realizes that his client is not present, leaving his slick and somewhat shifty assistant Martin Stett (Harrison Ford) to accept the tapes and provide the payment of $15,000. Something about not handing over the tapes directly to the director as originally agreed upon does not sit well with Harry. This triggers a tense and awkward confrontation where he struggles to wring the envelope from Stett’s hands, who in turn warns Harry that the tapes are “dangerous.” Harry leaves the building but not before spotting the two people who had the conversation of interest, Mark (Frederic Forrest) and Ann (Cindy Williams).

Harry meets Martin Stett to deliver the tapes

His curiosity aroused and his suspicions raised, Harry returns to his workshop to scrutinize tapes. Their content suggests possible clues that Mark and Ann, who happens to be the director’s wife, may be having an affair that could put them in danger. Here Harry is breaking his cardinal rule to not question or otherwise get involved in his clients’ lives. He obsessively scrutinizes Ann’s and Mark’s conversation, which seems to encompass small talk, moments of fear, nervousness, and vague references to plans of some kind.

Harry’s workshop is tucked away in what appears to be a former warehouse or factory, where he and Stan work on refining recordings for their clients. For much of the film Harry is poring over the tapes to uncover a potential danger and hopefully save Mark and Ann. His paranoia, inferences, and the weight of his guilt drive the rest of the story as he must decide if sharing these recordings will put people in mortal danger.

I won’t reveal much more, only to say that as Harry continues to probe, he will be compelled to step out of his strictly cultivated world of inward privacy; this will lead him into very uncharted territory with unforeseen consequences lurking around the bend.

About Harry

Gene Hackman’s Harry Caul is in virtually every scene in this film, so it’s only fitting that we spend a little time getting to know him—as best we can. You see, Harry is a very private person who holds his anonymity sacred. He bristles at and rebuffs attempts by his landlord, colleagues, and even his girlfriend to get him to open up. Harry simply doesn’t let people in. We do know that he is a practicing Catholic who goes to confession, has no patience for blasphemy, and is saddled with feelings of guilt over a previous job that may have gotten people killed. This factor weighs heavily on Harry and is the motivating force behind most everything he will do throughout the film. His one outlet seems to be jazz, and we see him unwind and disconnect as he plays his saxophone accompanied by his favorite records. These limited but stark moments in the film provide Harry with a reprieve from an otherwise tightly-wound and hyper-focused existence.

The World of Private Surveillance via The Conversation

I want to briefly mention a couple of standout sequences where we get to “spy” (I couldn’t help myself) on the private surveillance world and the cast of characters that inhabit it.

Bernie, Paul, and Harry at the Security and Surveillance Conference.

The first is a gathering of surveillance experts and vendors at the Security and Surveillance Conference, where we are introduced to the various gizmos, gadgets, and trickery used to eavesdrop on the unassuming. By all appearances it is an unseemly maybe even sleazy world that is nonetheless fascinating. Here we get to know those in Harry’s sphere, including Paul (Michael Higgins), an affable former cop who helps Harry on occasional jobs, and Bernie (Allen Garfield), an over-eager entrepreneurial wire tapper recently arrived from the east coast with a very big chip on his shoulder. It is at this trade show that we realize that Harry is kind of a big deal; his fellow buggers constantly attempt to get his ear or leverage his expertise.

There is also much to unpack in the subsequent sequence as Harry hosts a post-convention party at his workshop with Stan, Paul, Bernie, and a few others including a convention showgirl by the name of Meredith (Elizabeth MacRae). Meredith flirts with Harry throughout the evening with a curiously singular, dogged focus. As Harry and his guests drink, trading stories and bugging techniques, Harry’s anxieties and limited emotional intelligence come to into focus. Perhaps the only moment when an otherwise reserved Harry comes alive is when he gets caught up discussing the craft of surveillance, regaling his guests of the tricks he employed on his most recent job. Bernie and Harry also engage in a dance of inquisition and deflection. Bernie continues to press Harry to reveal trade secrets, while Harry sidesteps his queries. It’s a great scene that accentuates Harry’s inner anxieties and Bernie’s jealousy and ambition. It also allows the viewer an intimate behind-the-scenes glimpse of the private surveillance world and its community.

Stan, Paul, Bernie, and Meredith.

My two cents

The Conversation is a superb character study wrapped in a melancholy neo-noir package. It was directed by Francis Ford Coppola, who has referred to it as his most “personal” film. Later that year Coppola’s The Godfather Part II was released (you may have heard of it?). The Godfather films are arguably the movies most associated with the directing legend, but I feel that this under-the-radar film deserves a good amount of credit.

Gene Hackman is brilliant as the paranoid, exacting, and increasingly obsessed bugger par excellence—this is a surprise to no one who has enjoyed his many decades of work. Folks familiar with Hackman know he can pretty much do it all: from playing the heavy, the inspirational figure, the everyman, and even tackling comedic roles like he did in The Birdcage. He is a fearless actor willing to take on roles regardless of the unique challenges they present. Hackman simply is Harry Caul and I have difficulty imaging anyone else in this role. It must have required a great deal of restraint from Hackman to portray someone as emotionally stifled and insulated as Harry, and boy did he nail it!

Harry setting up for some surveillance

John Cazale is another heavy hitter for me, though his career ended far too early with his premature death. Cazale plays open, sensitive, and wounded characters so well. He brings depth and vulnerability to Stan, who in some ways is Harry’s opposite: much more willing to put himself out there and often seeking meaningful connections with those around him. He clearly admires Harry, though he is often frustrated at his thwarted efforts to both learn from and befriend him. Harry regularly browbeats or lectures Stan, clearly enforcing the power dynamic between the two. Stan yearns to be treated as a true partner, an equal, and a friend, and the sting he feels from Harry’s unrelenting high standards comes across clearly through Cazale’s compelling and raw performance.

Stan trying to read Harry

The rest of the film’s supporting cast also delivers solid performances, including Harrison Ford, Cindy Williams, and Frederic Forrest. A few years later Forrest would turn in a strong performance as Jay 'Chef' Hicks in Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979). A young Teri Garr also shines in a small part, playing Harry’s girlfriend; sadly, we lost Garr just this fall at the age of 79. Elizabeth MacRae is great in the role of Meredith, as she manages to be aggressive, vulnerable, and inscrutable all at the same time. She had a very successful career on TV, appearing in many westerns and shows such as Gomer Pyle and the long running soap General Hospital. MacRae passed away earlier this year at the age of 88.

The musical score by David Shire includes variations on a single piano theme, with subtle hints of jazz and ragtime. The recurring theme evokes an overcast drizzly day and nails a pitch-perfect noir tone that manages to be both captivating and downbeat. The score also ramps up with an electronic-infused stinger in some high-tension moments. At the risk of sounding incredibly cliché, the score in this film is a character of its own, much like Nino Rota’s score for that other Coppola film. Shire’s music is featured in another excellent crime thriller that we will be covering in this Cinematic Semicentennial series.

The Conversation at 50

The Conversation received three Academy Award Nominations in 1975, including Best Picture, as well as the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. Though received very well by critics, it was not considered a financial success, bringing in $4.4 million at the box office. Some of the highest grossing releases of 1974, outdoing The Conversation many times over, were a pair of Mel Brooks comedies (Blazing Saddles and Young Frankenstein), and the star-studded disaster epics The Towering Inferno and Earthquake.

Several excellent retrospectives and fresh reappraisals have been published this year to align with the 50th anniversary of the film’s theatrical release on April 7th. These essays explore emerging themes of the late 1960s and 1970s, including a growing distrust of government institutions and corporations and the state of privacy for American citizens. A number of these pieces explore the film’s genesis, which predates the events of Watergate—a historic event that invites obvious parallels considering the subject matter and the time of the film. See the supplemental sections for links to some of these stories.

Of course, these and similar topics generated some excellent films in the 1970s that are sometimes cast as a subgenre known as “paranoid thrillers,” which centered on privacy, technology, espionage, and political overreach.

While The Conversation did eventually find a somewhat larger audience through retrospectives and occasional theatrical rereleases, I still sense that it’s an underseen gem especially in contrast to The Godfather films. I am always happy to introduce it to the uninitiated in all its understated, gloomy glory.

Harry investigates

Did you know?

John Cazale sadly died from cancer at the young age of 42. He only appeared in five films over a six-year period. However all his films garnered critical acclaim and awards, and all are largely considered classics by film fans. They include The Godfather, (1972) The Conversation (1974), The Godfather Part II (1974) Dog Day Afternoon (1975), and The Deer Hunter (1978).

Robert Duvall’s character has limited screen time in The Conversation. But those looking for more Coppola-Duvall greatness need not look far, as Duval’s Tom Hagen is a central character in the first two Godfather films, not to mention his memorable performance as Colonel Kilgore in Apocalypse Now in which he gives his notorious “I love the smell of napalm in the morning” monologue.

It was Coppola vs Coppola as The Conversation went up against The Godfather Part II at the 47th Academy Awards. The other nominees were Chinatown, Lenny, and The Towering Inferno. The Godfather Part II won Best Picture that year.

Cast (abridged)

Gene Hackman – Harry Caul

John Cazale – Stan

Allen Garfield – Bernie Moran

Frederic Forrest – Mark

Cindy Williams - Ann

Harrison Ford – Martin Stett

Elizabeth MacRae – Meredith

Robert Duvall – The Director

Teri Garr – Amy

Michale Higgins – Paul

Crew (abridged)

Producer – Francis Ford Coppola

Director – Francis Ford Coppola

Director of Photography – Bill Butler

Film & Sound Editor – Walter Murch

Screenwriter – Francis Ford Coppola

Music – David Shire

How did I watch?

Blu-ray Paramount

To help commemorate the milestone, Lionsgate Home Entertainment recently released a 50th-anniversary restoration in 4K Ultra HD + Blu-ray (which looks stunning, if this trailer is any indication). I don’t think I can resist picking this one up.

Artwork for 50th anniversary 4k UHD restoration by Lionsgate Home Entertainment

Running Time: 1h 53m

Rating: PG

Recommendations based on The Conversation

Blow Up (1966)

Klute (1971) *

The French Connection (1971)

The Paralax View (1974) *

Three Days of the Condor (1975)

All The President’s Men (1976) *

* These three films are sometimes referred to as Director Alan Pakula’s “Paranoia Trilogy.”

Supplements-

The Conversation at 50: Why the paranoid thriller is more relevant than ever (BBC)

The Conversation at 50: Francis Ford Coppola’s paranoid and predictive masterpiece (The Guardian)

John Cazale’s Barbaric Squawk (The New Yorker)