Welcome to the Neighborhood: The Stepford Wives (1975)

Cinematic Semicentennial Series – 1975 edition

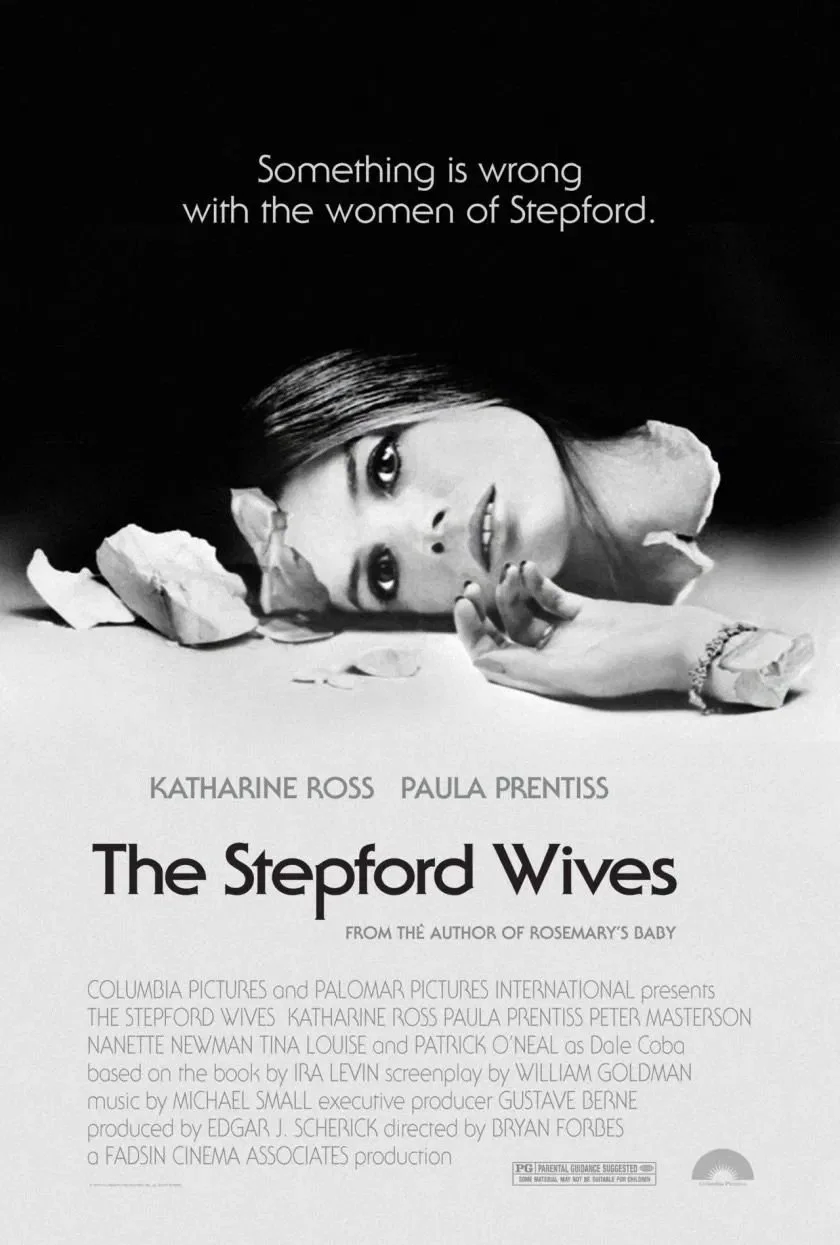

Original poster art

Our Cinematic Semicentennial Series is back with a classic science fiction film featuring a twisted take on domestic bliss. The Stepford Wives (1975) is the story of Joanna Eberhart (Katharine Ross), a photographer, wife, mother, and proud Gothamite whose relocation to suburbia is a dream nightmare come true. I’ve come to appreciate this film more with each viewing, and this last round gave me a lot to think about in relation to our current world climate.

Clean air, low taxes, good schools

Our film opens with Joanna, her husband Walter Eberhart (Peter Masterson), and their two school-age girls making a big move from a bustling Manhattan to the seemingly “idyllic” little town of Stepford, Connecticut.

Stepford checks all the right boxes for city folks chasing an idealized version of suburban life: plenty of open spaces, green fields, clean air, low taxes, good schools, and stately upper-class homes with doors that needn’t be locked at night. There is a historic precedence here as thousands of middle-class families left New York City in large numbers in the 1970s while the city grappled with high crime, unemployment, looming bankruptcy, and cuts in social services.

Despite moving into a roomy upscale home on a spacious property surrounded by manicured lawns, an ambivalent Joanna misses the vibrancy of New York; as it turns out, not everyone covets the homogenization of the suburbs. Walter on the other hand, a successful lawyer, is mostly excited about the relocation albeit with some reservations. We learn that Walter pretty much decided on the big move without consulting his wife in any meaningful way. This is a pattern in their relationship and real source of frustration for Joanna. The concept of men making important, even life-or-death decisions on behalf of the women in their lives is a powerful and prescient theme that runs through the entire film.

Joanna getting the kids to the school bus

Meet the Stepford Wives…and their husbands

The Eberharts’ respective experiences in their new home take two very different trajectories. Joanna, already restless and unhappy in Stepford, is confounded by the married women she meets. Nearly every one of the wives shares similar traits. Each is perfectly polite at all times and wears a placid if slightly dazed expression, as if on prophylactic doses of valium. They are also completely devoid of independent thought, as their only interests seem to be of the domestic variety, which includes shopping, baking, and obsessively cleaning. The only time a Stepford wife becomes more animated is when the topic of a new cleaning hack comes up, at which point she pivots to commercial testimonial mode as if plugging a new baking product or household cleaner. These moments are equal parts comical and eerie. It is also understood that a Stepford wife’s duties are not only to serve the sexual needs of her husband but to idolize him as a pinnacle of perfection.

While Walter is not 100% sold on Stepford at first, he is quickly recruited to join the Men’s Association, which is made up exclusively of white men of some wealth and privilege. Diz, a wealthy former executive at Disneyland who worked on the park’s animatronics, is also the president of the Association. On the surface Diz and the other members are busy with planning community activities and the restoration of the 19th century historic building that houses the Association offices. However, it appears that this group is behind Stepford’s carefully cultivated culture and the machine-like “condition” of their wives.

Walter is eventually let in on the dark secrets of the Association, and though he is jarred by the revelations, he seems willing to be a participatory member. In an interesting narrative choice, the vast majority of the time the viewer is not privy to exactly what the Association is doing, though we are given nonverbal hints throughout the film. I remain purposely vague in discussing these revelations as divulging any more could present the ultimate spoiler for anyone who has not seen or heard of this film. Suffice to say, something is amiss with the women of Stepford.

While Joanna finds the men of the Association to be mostly vapid, loud-mouthed bores, she reserves most of her animosity for Diz, sensing his inherent creepiness and chauvinism. This telling exchange upon their first meeting pretty much sums it up:

Diz: “I like to watch women doing little domestic chores.”

Joanna: “You came to the right town.”

Joanna: “Why do they call you Diz?”

Diz: “Because I used to work at Disneyland.”

Joanna: “No, really.”

Diz: “That's really. Don't you believe me?”

Joanna: “No.”

Diz: “Why not?”

Joanna: “You don't look like someone who enjoys making other people happy.”

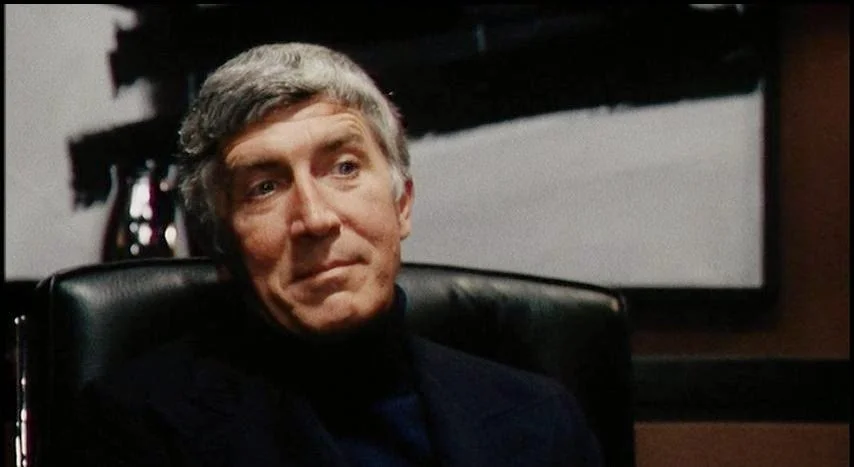

Left to right: Men’s Association members creeping around; Diz.

Joanna & Bobbie

Joanna eventually finds a kindred spirit in Bobbie Markowe (Paula Prentiss), who seeks Joanna out after reading a blurb about her photography in the local paper. Bobbie is a free spirit, bubbling with nervous energy and an irreverent sense of humor. Both ex-New Yorkers who miss the big city, the two become fast friends as they celebrate messy kitchens and entertaining ideas that fall outside Stepford’s carefully crafted social norms.

Inspired in part by the recent Women’s Liberation Movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s, Joanna and Bobbie attempt to form a consciousness group to offer the local women an outlet where they can talk about challenges in their marriages, finances, social dynamics, and more. While hardly having militant or grand aspirations, Bobbie and Joanna are hoping the ladies of Stepford will at least welcome an opportunity to vent. But the efforts mostly fall on deaf ears, as most of the wives are only interested In topics such as baking and cleaning.

Bobbie & Joanna: fast friends

Bobbie and Joanna come to understand that the women of Stepford did not arrive in the town as subservient housewives; rather, at some point, they are stripped of individuality and customized to serve their husbands. We witness some of these transformations ourselves, as the few remaining women are remade into dutiful Stepford wives.

Joanna and Bobbie cling to each other for support as the stakes are revealed to be even higher than they imagined. The two do some amateur investigations in the hopes of finding out how or why this metamorphosis occurs, while becoming ever more frightened, sensing that their time is almost at hand.

My two cents

The Stepford Wives is far from a perfect movie. It feels bit unfinished—like a freshly painted room that needed one more coat of paint to capture its true color. There are a handful of plot points that are not well fleshed out, which almost reads like post-production editing meant to reduce the run time (this is a conjecture on my part).

This not necessarily a taut, fast-paced thriller brimming with intense frights. Instead, director Brian Forbes gives us a sci-fi/horror film with a sun-drenched, breezy style that is almost casual in its delivery. That said, the movie has very sharp, unsubtle satirical sensibilities relevant to traditional gender roles, societal norms, and patriarchy. It also serves some very chilling content, especially once you learn the full ramifications of what is going on in this fictional Connecticut town.

The underlying dread in this film stems from the idea of losing oneself; that sooner or later you will no longer be you and that those around you will no longer be who they once were. It is the existential fear that any of us, including friends or loved ones, could be replaced, subsumed, or simply erased by insidious or clandestine forces outside of our control. This theme drives many classic science fiction films including Invaders from Mars (1953), Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), and the latter’s 1978 remake by the same title. Anxieties that humans will be challenged, even replaced, by advanced technologies that we created is also a theme that is prevalent in this film and others of the time, including 2001 A Space Odyssey, (1968), Colossus the Forbin Project (1970), and Westworld (1973).

Technology, which informs a major plot point The Stepford Wives, is often associated with progressive social advancement, but it can also be employed to turn back the clock in a regressive direction—this is a theme that resonates today. To that end, I recommend a great little article from Dame magazine that digs into the relevancy of The Stepford Wives in the age of the “tech bro.” Check out the supplements to link to this piece.

The cast of The Stepford Wives is one of its strong points, starting with Katharine Ross’ multi-layered performance as Joanna Eberhart. Joanna is smart, assertive, and quite relatable in her struggles with confidence when it comes to searching for a creative breakthrough as a photographer. While Joanna has a degree of agency, she also seems out of her depth as she runs up against the nefarious nature of Stepford. Ross’s large brown and enveloping eyes somehow feel central to her character, physically signaling her individuality and pulling us toward her humanity. She navigates the line between Joanna’s independence and suffocation brilliantly.

Peter Masterson’s performance as Walter Eberhart is also interesting. While he seems to be on board with the diabolical plans of the Men’s Association from the get-go, he projects moments of understanding and regret that feel authentic. If his behavior was truly meant only to lull Joanna into false sense of security, then he is even more duplicitous than we could have imagined. He also feels like a buttoned-up mismatch for his curious, creative, and free-spirited wife. Stepford’s unsettling qualities aside, this is a look at a couple grappling with a lack of commonality and genuine connection.

Paula Prentiss’s Bobbie is the antithesis of most of Stepford’s populace for her quirkiness, goofball manner, and irreverent sense of humor. Hers is a poignant performance as she and Joanna cling to each other for comfort, support, and sanity in a town that is stifling in its conservatism, banality, and ultimately its degeneracy. Patrick O'Neal maximizes his limited screen time as Diz with an unequivocally smug, leering, and sinister performance. I really enjoy the supporting cast playing both the ultra-vanilla homogenous wives and the conniving husbands of the Men’s Association, all of whom help to deliver sharp if unsubtle satire, social commentary, black humor, and horror.

I must imagine costume designer Anna Hill Johnstone had some fun with the starkly contrasting styles of Joanna and Bobbie in their jeans, midriff tops, overalls, and bandanas and the old-fashioned look of the Stepford housewives with their push up bras, high-necked dresses, ruffles, and sun hats. Diz often sports a black blazer and turtleneck, unequivocally manifesting the part of the classic villain. Sometimes, visual cues do much of the character work in a film, and that is very true here thanks to Johnstone’s excellent costume work.

Most of this film takes place in the confines of Stepford, which features bright saturating sunlight, green trees, and tall grasses swaying softly in the breeze. Cinematographer Owen Roizman in essence captures those more lazy and leisurely summer days, which belie the darker machinations of the town and the looming threat to its married women.

The Men’s Association

One striking visual moment of horror comes towards the climax of the film. We are treated to an exterior shot of the Men’s Association headquarters, a historic building resembling a small gothic castle. Joanna looks on, standing alone and shrouded in near darkness as rain comes pouring down in sheets. This shot is so effective precisely because it stands in stark contrast to the bright photography that bathes much of the film. It is a chilling, atmospheric sight worthy of a good horror movie. This is not the first time we have talked about Roizman; we met him back in January when we featured The Taking of Pelham One Two Three. Roizman has shot many other classic films including The French Connection (1971), The Exorcist (1973), Network (1975), and Tootsie (1982), among many others.

International and U.S. lobby cards for The Stepford Wives

The Stepford Wives at 50

The Stepford Wives was adapted from a 1972 novel of the same title, written by the prolific author Ira Levin. Levin’s versatile published work ranges from thrillers, to comedies, horror, and science fiction. His definitive genre classics include A Kiss Before Dying (1953), Rosemary’s Baby (1967), The Stepford Wives (1972), and the The Boys from Brazil (1976), all of which were adapted to the screen.

Released in U.S. theaters nationwide on February 12, 1975, The Stepford Wives made approximately $4 million dollars at the box office. The movie was met with mixed reviews from critics and provoked debate in feminist circles. Prominent activist Betty Friedan was indignant as she felt the film was suggesting that the fictional town of Stepford was the way things ought to be. Others in the movement defended and even lauded the film.

The Stepford Wives clearly has staying power, as evidenced by its clear influence on other sci-fi and horror films and an avid cult following which has grown over the decades. “Stepford Wife” also made its way into the pop culture lexicon as code for a domesticated woman who is subservient, lacking independence, and focused entirely on the needs of her husband and keeping a house straight out of Better Homes and Gardens.

This would also not be the last word on Stepford as the ensuing decades would treat us to several follow ups on both the big and small screen, including Revenge of the Stepford Wives (1980), The Stepford Children (1987), The Stepford Husbands (1996), and a mostly comedic remake of The Stepford Wives in 2004. Jordan Peele has often cited The Stepford Wives, along with Rosemary’s Baby (1968), as having a major influence on his conception of his breakout sci- fi/horror thriller Get Out (2017).

Rosemary’s Baby and The Stepford Wives, both adapted from Ira Levin novels, would make a great, if chilling, double feature. Both movies center around female victims of some serious gaslighting and share several other themes. The Stepford Wives is as relevant as ever as some conservatives have been advocating for regressive policies that roll back reproductive rights and women’s ability to make decisions relevant to their own bodies. At the same time certain circles have been advocating for a return to so-called traditional values, emphasizing (to near fetishistic levels) that a woman’s primary role should be motherhood, above all else.

Science fiction cinema has been exploring the far-reaching implications of technologic advances for more than a century, with tales of robots, automation, artificial intelligence (AI), and near sentient androids. Again, and without giving away too much, this film wrestles with the question of technology’s dark potential. For a much more recent take on AI and androids, check out the sci-fi/horror/comedy Companion, which was released in theaters earlier in 2025.

Excerpts from the Michael Small score of The Stepford Wives.

Cast (abridged)

Katherine Ross – Joanna Eberhart

Peter Masterson – Walter Eberhart

Paula Prentiss – Bobbie Markowe

Josef Sommer – Ted Van Sant

Nanette Newman – Carol Van Sant

Tina Louise – Charmaine Wimpiris

Franklin Cover – Ed Wimpiris

William Prince – Ike Mazzard

Patrick O’Neal – Dale “Diz” Coba

Crew (abridged)

Director – Bryan Forbes

Screenwriter – William Goldman

Production Designer – Gene Callahan

Director of Photography – Owen Roizman

Film Editor – Timothy Gee

Music – Michael Small

Costume Designer – Anna Hill Johnstone

How did I watch?

Streaming on Tubi

Running Time: 1h 55m

Rating: PG

By Columbia Pictures - The Sacramento Bee, January 19, 1975, Public Domain

Did you know?

Fans of classic TV may recognize Tina Louise, who plays the Stepford wife Charmaine. Louise is best known for playing the red-headed bombshell Ginger on Gilligan’s Island (1964-1992).

The fictional Men’s Association Building is the historic 19th century Lockwood-Mathews mansion in Norwalk, Connecticut. The site is now a museum.

Screenwriter William Goldman won the Oscar for best original screenplay for Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid (1969) and best adapted screenplay for All The President’s Men (1976). He also adapted screenplays from some of his own novels including the thriller Marathon Man (1976), the offbeat horror film Magic (1978), and the beloved fantasy The Princess Bride (1987). Goldman also adapted the Stephen King novel Misery; the film features Kathy Bates and the late James Caan (1990).

Diane Keaton was being considered for the role of Joanna and allegedly dropped out when her analyst/therapist read the script and deemed it to have “bad vibes.”

Before arriving in Stepford, Katharine Ross was featured in two iconic films of the late 1960s: The Graduate (1967) and Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid (1969).

Dee Wallace, who is loved by many genre fans, can be spotted making her super brief film debut as Charmaine’s maid Nettie. Wallace would soon be a fixture in sci-fi and horror films of the ‘80s including The Hills Have Eyes (1977), The Howling (1981), ET (1982), Cujo (1983), Critters (1986), and The Frighteners (1996).

The film was shot in Connecticut in places like Darien and Fairfield.

Actor Peter Masterson’s daughter—Mary Stuart Masterson—makes her acting debut in the film playing Walter & Joanna’s seven-year-old daughter.

Recommendations based on The Stepford Wives

Metropolis (1927)

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956)

Westworld (1973)

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978)

Bladerunner (1982)

Ex Machina (2014)

Companion (2025)

Supplements-

The Disturbingly Prophetic Message of ‘The Stepford Wives’ (Dame)

The Chilling Horror Satire That Was Unfairly Overshadowed by Its 2000s Remake (Collider)

The Stepford Wives: Inside the Making of the 1975 Feminist Horror Classic (Entertainment Weekly)