“This wasn’t meant to be a game!”: Rollerball (1975)

Cinematic Semicentennial Series – 1975 edition

For this latest installment of our Cinematic Semicentennial Series, we head to the arena as we explore a futuristic sport and corporate society fully realized. We’ve seen many visions of the future—ideal and dystopian—and this movie definitely lands square in the latter category. So gear up, tighten those skates, and let’s hit the track for some Rollerball!

Corporate rule

It is the year 2018. Giant multinational corporations now oversee the world’s affairs since the bankruptcy and collapse of all nation states. Corporations administer infrastructure, food, housing, communications, and other services to people around the world. This evolution towards a corporate society has, so we are told, ensured a world without war, disease, or want. There also exists a privileged class of elites who attend decadent parties and have access to various amenities, including a steady supply of recreational drugs in the form of tiny white pills that they pop like Tic Tacs.

These corporate overlords are represented by the Houston-based Energy Corporation and its erudite chief executive Bartholomew (John Houseman). As Bartholomew sees it, the corporations take care of everything and all they ever ask of anyone is that they do not interfere with management decisions. In order to limit the introduction of ideas that might rock the boat in that regard, these corporate tycoons have largely eliminated books in their original form. Instead, there exist transcribed, edited, summarized, and/or classified versions in “libraries” at sleek luxury centers accessible only by those authorized. And to ensure citizens do not get too curious or too frustrated with the status quo, we have one sporting diversion: a gladiatorial-style game known as Rollerball.

The only game in town

What is Rollerball you might ask? Simply stated, It is a bruising and unforgiving amalgam of rugby, roller derby, hockey, and motor cross. Each company-controlled team, named after a home city, is composed of 18 players—10 starters and 8 substitutes.

Players are outfitted with knee, elbow, and shoulder pads, helmets, black leather pants, and gloves with silver spikes. The game is played on circular track with a challenging 35-degree slope. Starting lineups include seven players on roller skates and three on motorcycles with shields and towing bars. The objective of the three-period game is for teams to skate/ride counterclockwise and scoop up a steel-coated ball shot onto the track. Two skaters, also designated as catchers, wear thick leather gloves to be able to scoop the ball without having their hand destroyed.

The team that possesses the ball must make their way around the track in the hopes of throwing or placing the ball into a magnetic target along the railing at the high end of the track. While the offensive team attempts to escort (the motorcycle tow comes into play here) and defend the ball carrier until he can take a shot at the target. Meanwhile the defending team does whatever they can to disrupt the caravan and take down the ball carrier. Aside from the occasional penalty, athletes are permitted to employ nearly any tactic against competing rollerballers including tripping, drop kicking, chopping, and punching, while cyclists may slam into each other and even drive over prone skaters. And here’s the kicker: the rules of the game can be changed at the whim of the governing corporations.

The undisputed top athlete of Rollerball is Jonathan E. (James Caan), who plays for Houston, also known as The Energy City. Jonathan plays with laser focus and a mean edge, just as effective at knocking out opposing players as he is at scoring. As captain and the face of Rollerball, Jonathan enjoys many perks including a spacious ranch home, horses, private helicopter transport to games, and what is essentially a corporate-assigned concubine. We learn that early in his career Jonathan’s actual wife Ella (Maud Adams) was taken away from him by a covetous corporate executive; Ella may have left on her accord though it is never clear. Jonathan’s closest companion on the team is Moonpie (John Beck), a towering player known for his swoop move where he skates down from the top rail to drop kick opposing players.

I realize we spent a bit of time talking about the game itself but that is because it figures so prominently in the story. In fact, three matches serve as the centerpieces of the three acts as Houston squares off against Madrid, Tokyo, and New York.

“Jonathan! Jonathan! Jonathan!”

While Bartholomew publicly heaps praise on Jonathan and the Houston team, he privately informs his star player that the Executive Board of the Energy Corporation wants him to retire. Bartholomew couches this as a good thing with several advantages: a glitzy and publicly broadcast retirement show honoring the star’s stellar 10-year career, plus continued access to all the material comforts including a literal privilege card that opens the doors to so-called luxury centers. Jonathan balks at the request, especially since it is not clear who makes decisions at the corporate level and why. Jonathan is also reluctant to pack it in before the upcoming semifinal game against Tokyo, a challenging team with an unorthodox style of play.

Bartholomew employs flattery, enticements, and even threats on an unceasingly defiant Jonathan, who searches for answers as to why corporate wants him out. Soon enough, however, Bartholomew reveals the answer: Jonathan excels just a bit too much in Rollerball, a game that man was not meant to grow strong in. But the Houston captain has indeed grown strong, as chants of “Jonathan! Jonathan!” can be heard at every game. Such a public display of individual strength could inspire the masses and represent a threat to the order of things.

I am including this telling excerpt from a scene where Bartholomew is addressing all the corporate higher-ups on virtual screens (a precursor to Zoom) regarding what to do about Jonathan E.:

“In my opinion, we are confronted here with something of a situation. Otherwise, I would not have presumed to take up your time. Once again, it concerns the case of Jonathan E. We know we don't want anything extraordinary to happen to Jonathan. We've already agreed on that. No accidents, nothing unnatural. The game was created to demonstrate the futility of individual effort. And the game must do its work. The Energy Corporation has done all it can, and if a champion defeats the meaning for which the game was designed, then he must lose. I hope you agree with my reasoning.”

Meanwhile Jonathan enlists his former coach and mentor Cletus (Moses Gunn), now a corporate executive, to find out why the corporation wants him out. Cletus explains that while decisions are kept quite secret there is a real sense that the executives are afraid of Jonathan and what he represents. The Rollerball playoff finals are set, Houston vs. New York, with no penalties, no substitutions, and no time limit. The deck has been stacked against Jonathan, ensuring a bloody finale that is less about competition and more about survival. And it is all summed up by his coach when exclaims, “This wasn’t meant to be a game! Never!”

My two cents

Rollerball is a dystopian sci-fi film that also teases a utopian future whereby war, disease, and poverty have been eradicated—or so we are told by the corporate executive class. One drawback of the film is that we never get a true sense of what life is like for the rest of the population. Does everyone truly live well? Corporate society, which Bartholomew describes as “inevitable,” takes care of everything so long as no one, not even Jonathan E., interferes with their decisions. Of course, he does just that, which provides the primary conflict of the film. There are also references to earlier tribal and corporate wars but we, just like Jonathan, are not privy to that history.

The story of Rollerball, like much of sci-fi cinema, hinges on a big “what if?” Today, powerful corporations hold great sway over ostensibly sovereign governments, driving policies and priorities, and not always to the benefit of most humans or the planet they inhabit. But what if circumstances allowed this pretense of sovereignty to be dropped and major corporations simply replaced governments altogether? What would that look like? It’s an intriguing if fraught premise that Rollerball and some genre films/TV shows have explored. The first one that comes to mind is the excellent new sci-fi show Alien Earth, which presents a future of fully realized corporate power and a world inhabited by humans, synthetics humans, cyborgs, and a collection of interstellar beasties. We’re pretty psyched to hear it’s been renewed for second season!

Rollerball’s narrative can be a bit frustrating at times, as the delivery of certain story elements feels vague and half-baked. The film dabbles in some interesting themes—comfort vs. freedom, individuality vs. conformity, and humanity’s insatiable desire to consume violence—all of which are pitfalls of a corporate-centered society. However, fans looking for deeper exploration into these subjects may be disappointed as these themes are largely explained via dialogue (much more telling than showing). The biggest exception would be glimpses of the indulgent life of corporate elite. One scene that stands out is when Jonathan is being honored at a lavish party. We are confronted with how decadent and vacuous life has become as party goers pop pills and “company women” hang about their male assignments. There is one notable sequence in which a group of party goers, drunk, and/or high take a futuristic laser gun outside to incinerate some innocent trees. We watch them laugh and carouse as the trees burn. Arguably, the most arresting and disturbing shots of this sequence are of the female guests wearing expressions of torment, sadness, and resignation. And you see that throughout the party. Something is not quite right.

The athletic actor James Caan is well cast as the increasingly confused yet defiant Jonathan E. I have to say that I initially found his performance a bit confounding as he often speaks under his breath in a whispering tone to the point where I had difficulty understanding him. However, I watched an interview with Caan years later in which he explained that Jonathan’s subdued performance was intentional. His character was a company-raised athlete, meant to be a lean and mean rollerballer on the track who revels in his luxuries when off—and not much else. Critical thinking and expression are simply not things that have been fostered in him, so that when he is confronted by the will of the corporation and their clandestine operations he is bewildered at first. While Caan largely sustains a vaguely Southern accent (Houston and all), there is one moment where the New Yorker in him comes out, and we are suddenly reminded of one of his most famous roles: Sonny Corleone. You will know it when you hear it.

John Beck is well cast as the imposing, folksy, and none-too-clever Moonpie, a loyal friend and teammate. Moonpie revels in being a rollerballer and fanaticizes about a life of luxuries that his friend takes for granted. John Houseman, truly one of a kind, is delightful as our corporate villain Bartholomew: sometimes charming, sometimes smarmy and officious, and always busy with behind the scenes machinations to enforce the will of the major corporations. Moses Gunn is also memorable as Cletus, Jonathan’s former coach and friend-turned-executive placed in the awkward position of trying to sleuth for his mentee without running afoul of the powers that be. I also want to mention a couple of actresses who play company women: Barbara Trentham as Daphne and Pamela Hensley as Mackie. They hold small but effective roles portraying women strained, stressed, and strung out for having to live a life of posh servitude.

The music for Rollerball was conducted by André Previn and performed by the London Symphony Orchestra. It features a couple of very well-known classical pieces, including Johan Sebastian Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D minor, which most of us associate with old-school horror. The piece is featured in classic chillers like Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1931) and The Black Cat (1934), among others. Then there is Tomaso Albinoni’s Adagio for Strings which plays during several of the scenes between Jonathan and Ella. This beautiful piece invokes high drama and tragedy and is used to absolute perfection in Peter Weir’s incredible World War I drama Gallipoli (1981) as a unit of Australian soldiers prepare for a suicidal attack on a set of Turkish trenches. I associate both pieces so strongly with other genres and films that I feel thrown off by their inclusion in Rollerball (but that’s my problem to get over).

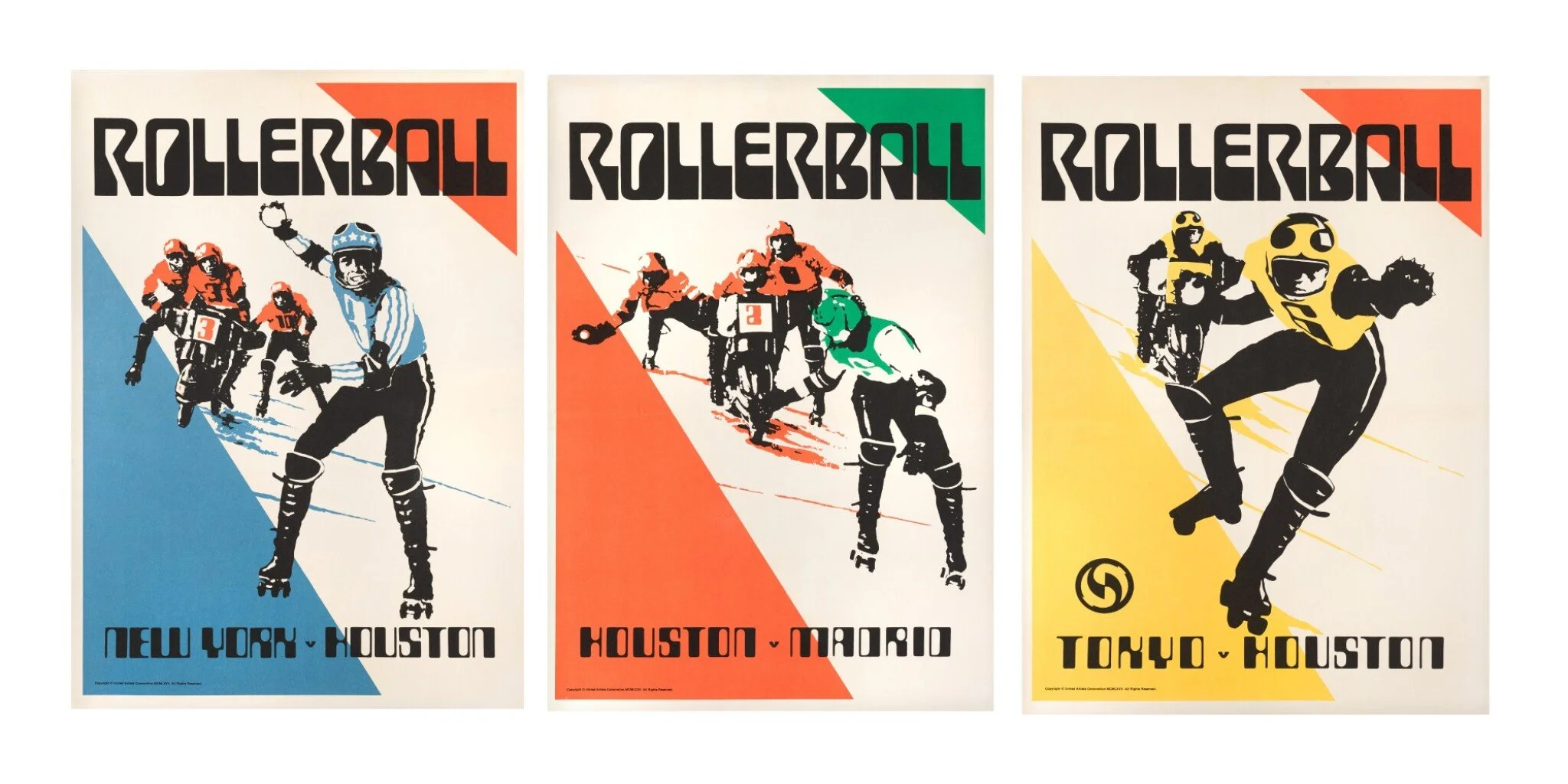

Promotional artwork.

The production took full advantage of on-location shooting around Munich (in West Germany at the time), which featured the futuristic-looking facilities used for the 1972 Olympic games, including the Olympic Basketball Arena where all Rollerball scenes were shot. The space was refitted with the sloping track, a key design element. The recently built BMW Headquarters building with its triple cylindrical towers doubled as the Energy Corporation offices. Props also to the set design and costume design showcasing fan swag, including t-shirts, hats, and flags for each of the teams.

The events of Rollerball are structured around three big games, occurring at the beginning, middle and end of the film with increasingly high stakes and violent playoff matches pitting Houston against Madrid, Tokyo, and New York in that order. These bloody contests are the highlights of the film. While some filmmakers today might be inclined to infuse more elaborate and refined choreography, director Norman Jewison and his team opted for gritty, grounded, and chaotic action befitting a game designed to put humans in their place while serving up visceral competition for the fans. That is not to say that the events on the track are not exciting. As players skate hard, kick, punch, crawl, glide, collide, and wipe out, faces are bloodied, bones are shattered bikes crash and explode, and our primal sides wince—all while executives look on with great concern, fans hang on every move, and stakes are raised.

Rollerball would not be the film it is without all the incredible stunt work, so I was glad to see that much of the stunt team, led by Craig R Baxley and Chuck Parkinson Jr., appear in the credits. Also contributing to the authentic feel of this fictional sport were actual multinational roller derby players, German speed skaters, and Irish roller hockey players. From what I understand the American stunt team got along famously with them all.

Rollerball at 50

Rollerball was released in U.S. theaters on June 25, 1975, ultimately earning approximately $30 million at the box office against a budget that hovered in the $6 million range. The film was based on a 1973 short story in Esquire magazine by William Harrison, who also wrote the screenplay. The movie has earned its place among the dystopian science fiction cinema of the late 1960s to the mid 1970s, which saw humanity’s achievement of a truly enlightened society to be a dubious proposition at best. As we currently grapple with a regressive government inclined towards authoritarianism while major corporations take up most seats at the table, I feel that the distrust is founded. Other films of the period that share a similar approach include THX 1138, Colossus the Forbin Project, Soylent Green, and Logan’s Run.

Death Race 2000, which was released earlier the same year, entertains some of the same themes albeit with a wildly different tone that leans into comedy and satire. Concentric Cinema was all over this Roger Corman-produced gem this past spring.

Director Norman Jewison had an eclectic filmography before and after Rollerball with credits including The Cincinnati Kid (1965), In the Heat of the Night (1967), Fiddler on the Roof (1971), Jesus Christ Superstar (1973), And Justice for All (1979), A Soldier’s Story (1984), Moonstruck (1987), Only You (1994), and The Hurricane (1999). Jewison passed away in January of 2024 at the age of 97 while James Caan left us in 2022 at the age of 82.

During a recent appearance on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, Keanu Reeves, no stranger to sci-fi/action cinema, cited Rollerball as his favorite action movie growing up.

There is a 2002 remake that I have yet to hear or read a good word about from critics or fans; I think I’ll skip it.

Cast (abridged)

James Caan – Jonathan E

John Beck – Moonpie

John Houseman – Bartholomew

Maud Adams – Ella

Moses Gunn – Cletus

Pamela Hensley – Mackie

Shane Rimmer – Rusty (Team Executive)

Barbara Trentham – Daphne

Ralph Richardson – Librarian

Crew (abridged)

Director – Norman Jewison

Screenwriter – William Harrison

Production Designer – John Box

Art Designer – Robert W. Laing

Costumer Designer – Julie Harris

Editor - Antony Gibbs

Cinematographer – Douglas Slocombe

Producer – Norman Jewison

Production Company -

How did I watch?

Shout Factory UHD

Running Time: 2h 5m

MPAA Rating: R

Did you know?

The cast of rollerballers participated in a mini boot camp, where they trained to be become strong skaters. However, it was a rough go for all once Caan and company attempted to skate on the slanted track with its challenging physics.

Sylvester Stallone was considered for the role of Jonathan E; while he didn’t land the part, he can be found in another dystopian sci-fi film, albeit a more farcical one: the aforementioned Death Race 2000.

The cast and crew spent 17 weeks filming, including studio work at Pinewood Studios in England and location shooting at Fawley Power Station in Hampshire.

The cast and stuntmen made up their own rules for Rollerball as they went along, which greatly adds to the real feel of the game.

There is one strange, memorable, and funny scene featuring AI entity Zero and his human counterpart, the eccentric and exasperated “Librarian” played by the great English actor Ralph Richardson.

Director Jewison purportedly cast James Caan as Jonathan E. after seeing him play Brian Piccolo, the real-life Chicago Bears running back, in the 1971 TV movie Brian’s Song. Caan starred opposite Billy Dee Williams, who played the great Chicago Bears running back Gayle Sayers.

When filming was completed, the stuntmen wanted to play a for-real game before the sets were struck, but the studio nixed the idea due to liability concerns.

The most fatalities ever recorded in a Rollerball game was nine (yikes) in a game between Rome and Pittsburgh.

The fastest ball ever fielded by a rollerballer? 120 miles per hour!

Rollerball’s excellent cinematographer Douglas Slocombe knows his way around action/adventure films having shot Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984), and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989).

Recommendations based on Rollerball

THX 1138 (1971)

Death Race 2000 (1975)

Logan’s Run (1976)

The Running Man (1987)

Supplements-

TCM - Tribute to Norman Jewison (YouTube)

‘Rollerball’ Turns 50! 7 Things You Didn’t Know About James Caan’s Dystopian Sports Film (Remind Magazine)

James Caan, ‘The Godfather’ and ‘Misery’ Star, Dies at 82 (Variety)