Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors: Werewolf (1965)

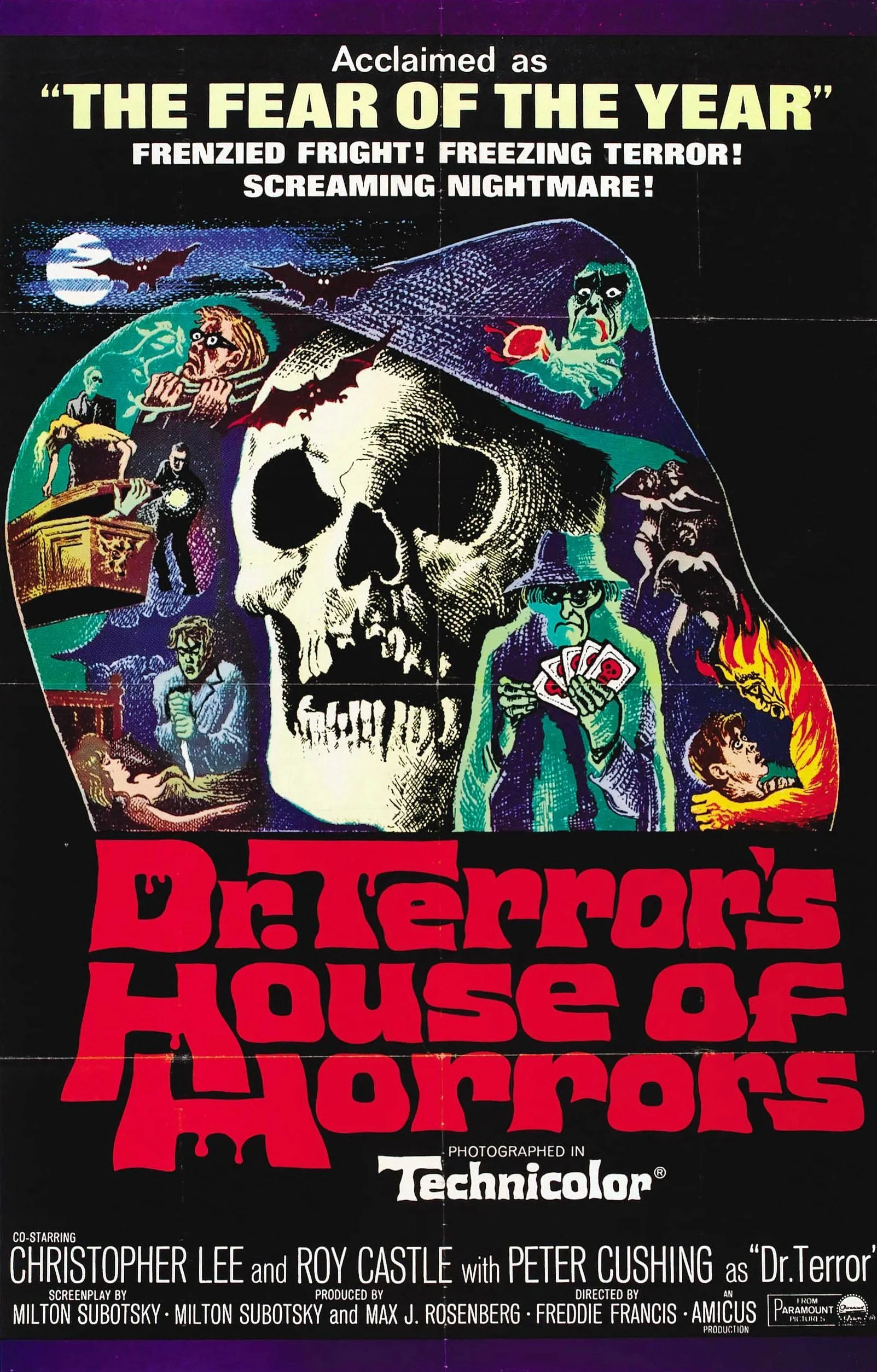

Original poster art

It occurred to me that it’s been more than a year since the launch of Concentric Cinema and we have yet to feature a horror anthology film. Frightening, I know! Horror anthologies are more of an appetizer, showcasing bite-sized stories that blend scares, monsters, ghosts, and smatterings of sly humor and camp. They are often framed by a wrap-around segment that houses three-to-five vignettes and include tales about particularly loathsome characters getting their comeuppance in a very satisfying and poetic way. While deep down we know that wishing harm on someone is—let’s just say, wrong—anthologies have a way of saying: it’s ok, treat yourself.

These anthologies date back at least 70 years beginning with the British supernatural horror film Dead of Night (1945), but the subgenre would blossom in the 1960s with a series of international releases. The U.S. brought us the Roger Corman-directed comedy/horror film Tales of Terror (1962), Italy graced us with Mario Bava’s gothic piece Black Sabbath (1963), and Japan gifted us Masaki Kobayashi’s beautiful and ghostly Kwaidan (1965). 1965 also saw the birth of a new player in the anthology horror space. The U.K.’s Amicus Production put out dozens of horror and science fiction b-movies of varying quality throughout the 1960s and 1970s. The studio became synonymous with horror anthology films, releasing seven of these between 1965-1974. Of course it doesn’t hurt that two undisputed titans of terror, the U.K.’s Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing, often appeared in these anthologies. Lee and Cushing would also star in many horror and thriller features for rival British studio Hammer Films.

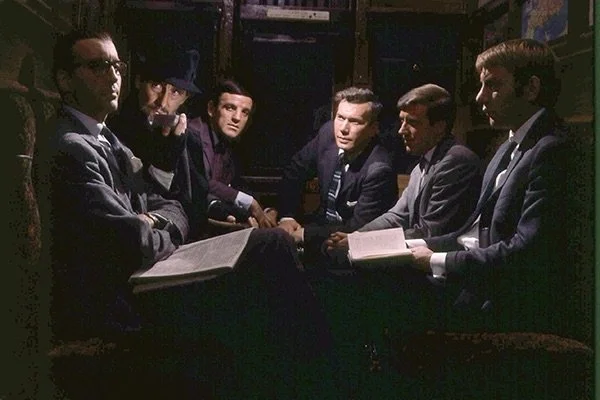

The movie that kicked off this run by Amicus is one beloved by many a monster kid and fan of classic era horror, Dr. Terror’s House of Horror’s (1965). Captured in rich technicolor, the film is based on a screenplay by screenwriter/producer Milton Subotsky and directed by the great cinematographer Freddie Francis. The wrap-around story is set in a train car with five passengers who are joined by a mysterious sixth by the name of Dr Schreck, played by the one and only Peter Cushing. Schreck, translated from the German as “fright” or “terror,” is a doctor of metaphysics and reader of tarot cards. As he explains (in a vaguely central European accent), the things he foretells can sometimes be terrifying, which is why he dubs the deck his “house of horrors.” He goes on to describe tarot as the key to ancient wisdom, a “picture book” of life and answer to the deepest questions of philosophy and history; since I know nothing about tarot cards we will just have to take Schreck’s word for it.

How exactly does the reading work? It is pretty simple actually: Dr. Shreck holds the deck up for the subject to tap three times, subsequently shuffles the deck, then draws four cards. While the four cards suggest a possible fate, a fifth hints at knowledge that might change the future if change is possible—and that’s a big if.

One by one Schrek engages his fellow passengers, drawing cards for each and thereby initiating the following vignette. First up is the curious architect Jim Dawson (Neil McCallum) who is most eager to have a go at the tarot. It’s three taps and we’re off into the first segment.

Werewolf

Cast:

Neil McCallum – Jim Dawson

Ursula Howells – Mrs. Deidre Biddulph

Peter Madden – Caleb and his granddaughter Valda

Katy Wild – Valda

Edward Underdown - Tod

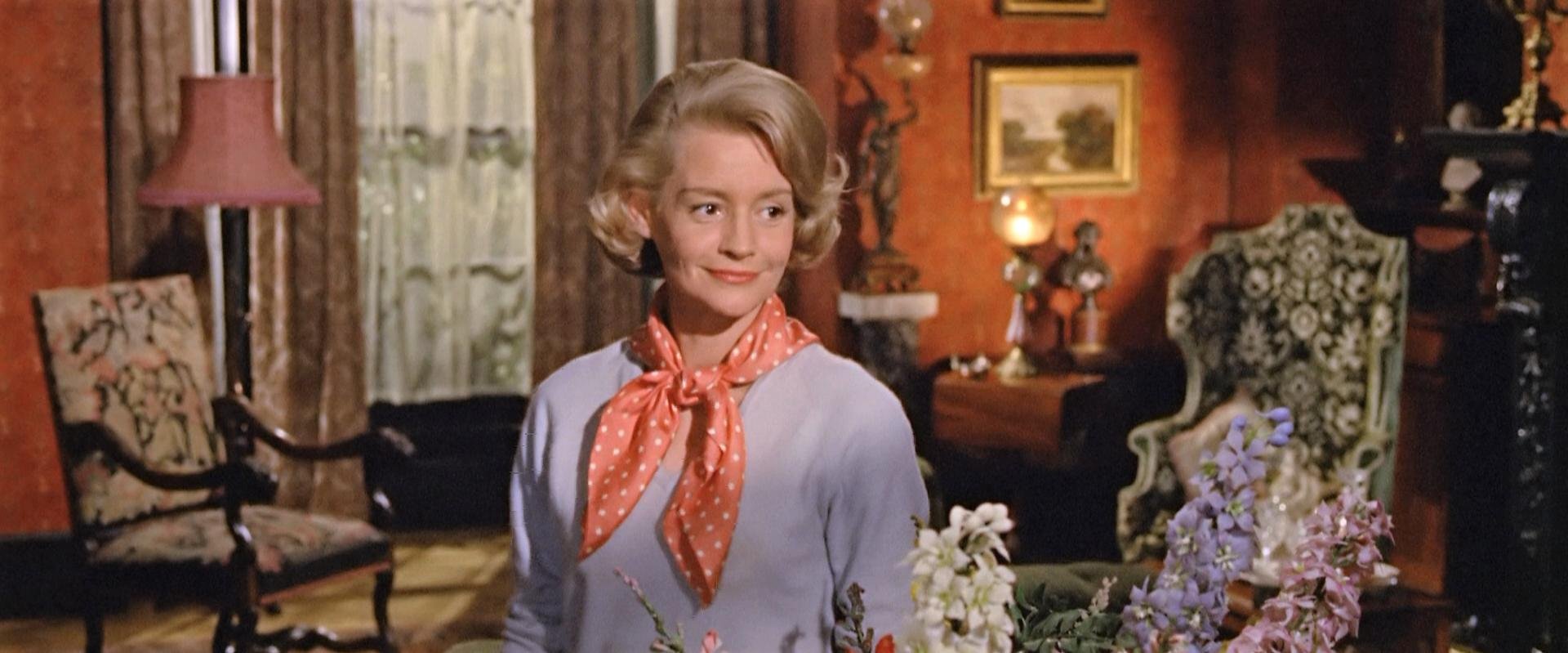

Dawson’s architectural firm sends him on a job to a remote island in the Hebrides, an archipelago off the northwest coast of Scotland. His assignment is to undertake renovations at the home of wealthy widower Mrs. Deidre Biddulph to help showcase her late husband’s archaeological discoveries. The house also happens to be Dawson’s ancestral home, which was in his family for a couple of centuries before he sold it to Mrs. Biddulph. Biddulph, who has a friendly, easy air about her, requested Dawson specifically for the project.

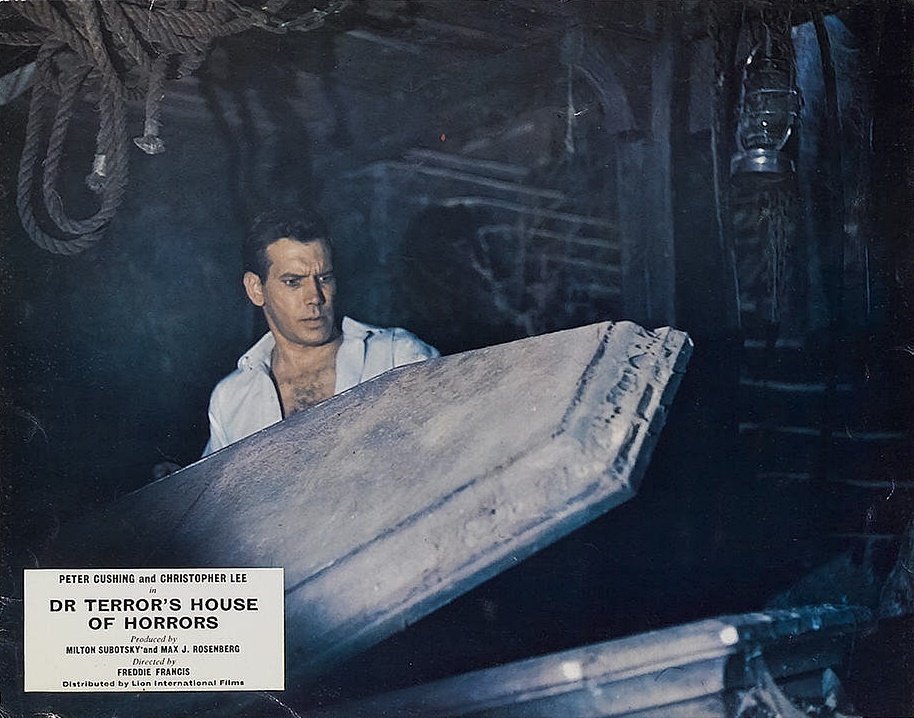

During a routine inspection of the house’s walls and foundations Dawson makes an astounding discovery. Buried behind plaster wall in the cellar is the 200-year-old stone coffin of the werewolf patriarch Cosmo Waldemar. The find is wrapped up in a legend: more than two centuries earlier Waldemar alleged that Dawson’s ancestors laid claim to the house which was rightfully his. He vowed that one day he’d return and that whoever owned the house would take Waldemar’s place in his coffin so that he could once again assume human shape.

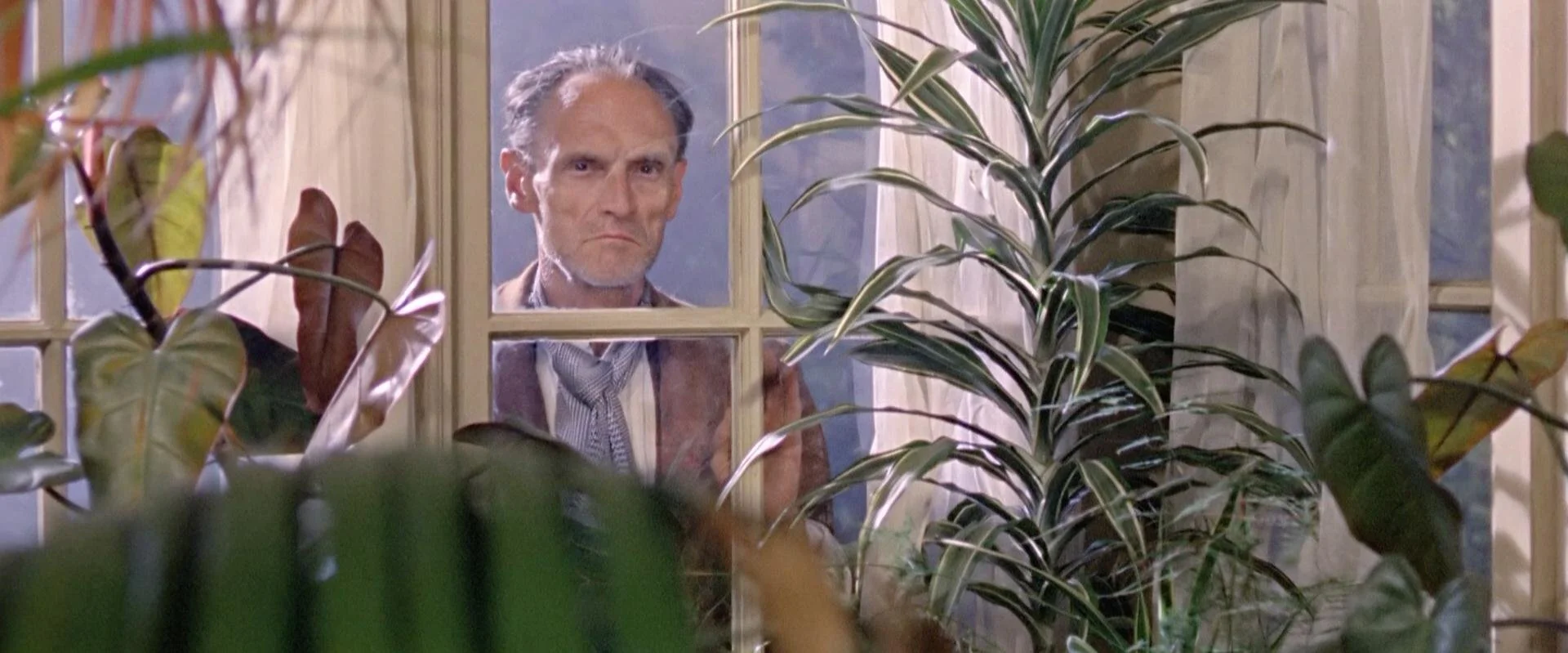

Having accepted the legend as fact, Dawson and the home’s longtime caretaker, a stoic man by the name of Caleb, attempt to investigate. In doing so they inadvertently allow Waldemar to escape his coffin. Dawson prepares for a lycanthropic confrontation with the help of some silver bullets forged from a family heirloom. Meanwhile Mrs. Biddulph carries on with a suspiciously breezy attitude about the frightening events unfolding around her home.

My brief take

Werewolf certainly has atmosphere in spades: an old fog-shrouded home on a remote island, eerie shadows, candlelit interiors, a cobwebbed cellar, and moody lighting all brought to life through rich technicolor. While the segment is light on the blood and gore, there is just enough for genre fans of the period to recognize that melted-crayon red so ubiquitous in the 1960s and 1970s.

As with many anthology segments, events unfold briskly and dialogue is delivered economically for some quick and dirty exposition that keeps the story moving. While the piece includes a bit of werewolf lore (e.g. silver bullets), it also evokes classic vampire mythology as coffins, curses, and immortality figure in this vignette. Those eager for some ferocious werewolf sequences that you can really sink your teeth into might be disappointed as the monster action and reveals are extremely sparse here. That said, there are some late revelations and a bit of a twist that help punch up the segment. While I found Neil MaCallum and Ursula Howells to be well cast as Dawson and Mrs. Biddulph, I was particularly drawn to Peter Madden as the grizzled, strong-jawed Caleb, a man of few words who seems to have seen a thing or two in his life.

Werewolf is a product of its time, coming at the tail end of the classic horror age. This style of filmmaking feels almost quaint when compared to the more visceral, provocative, and experimental horror soon to come in the late 1960s and 1970s. It is far from perfect but not without its charms.

lobby cards