The Big Heist that Wasn’t: Dog Day Afternoon (1975)

Cinematic Semicentennial Series - 1975 edition

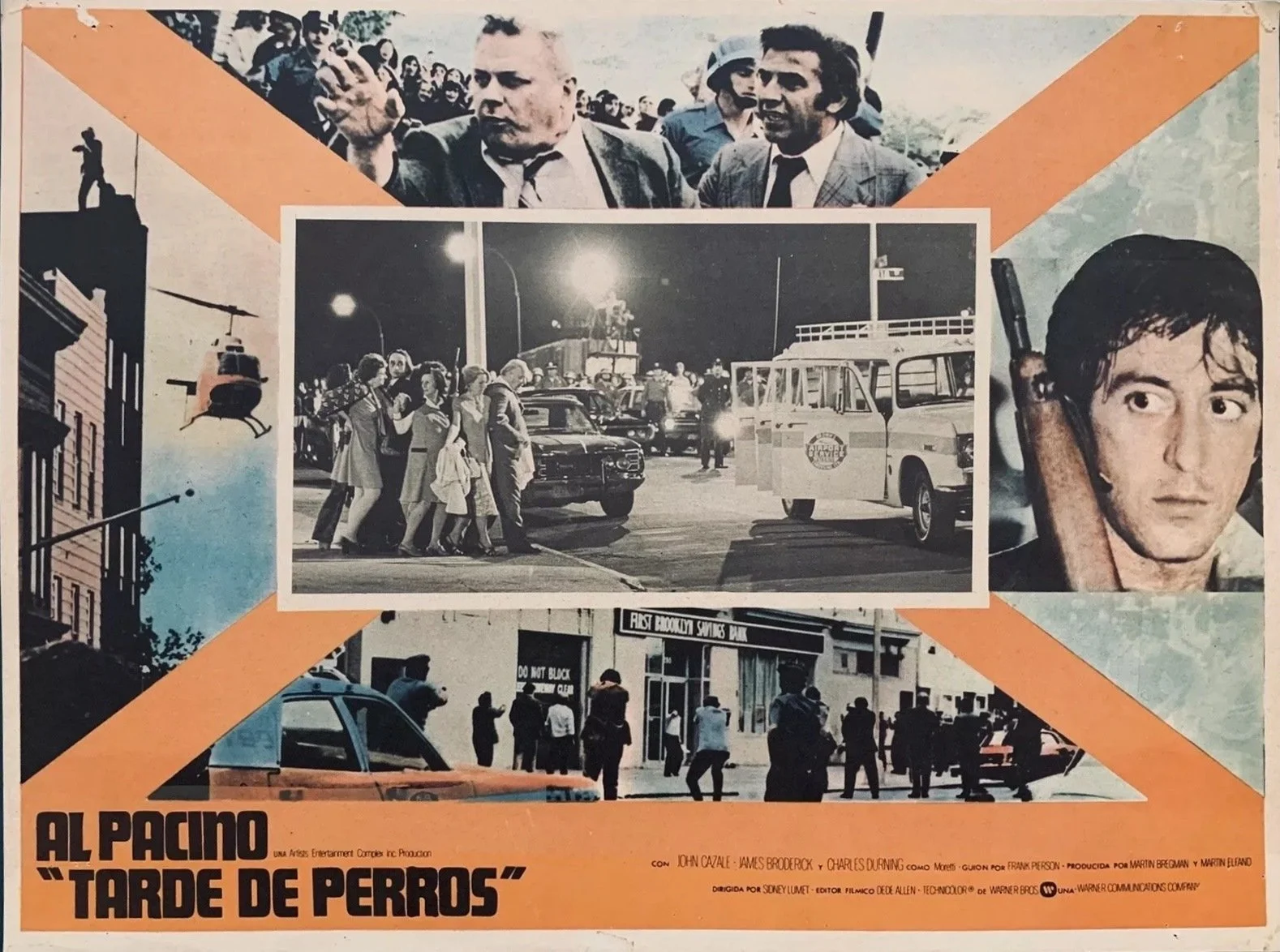

Original poster art

We simply can’t move on from 2025 without including one more entry in the 1975 edition of our Cinematic Semicentennial Series. It has been a cold, blustery late December/early January here in the northeast. But to set the right mood we ask that you throw on some light clothes and extra deodorant and travel back with us to the sweltering days of late summer as we explore Dog Day Afternoon.

The film was based on a real-life event in which two men, John Wojtowicz and Salvatore Naturile, bungled their way through a botched robbery and subsequent hostage-taking situation at a bank in Gravesend, Brooklyn on August 22, 1972. The sensational, “only in New York”-type story was featured in a Life magazine article entitled “The Boys in the Bank,” published on September 22, 1972. Going forward I will mostly focus on the fictionalized film version of this story but check out the supplements section for more information on the historical events.

Banking hours meet amateur hour

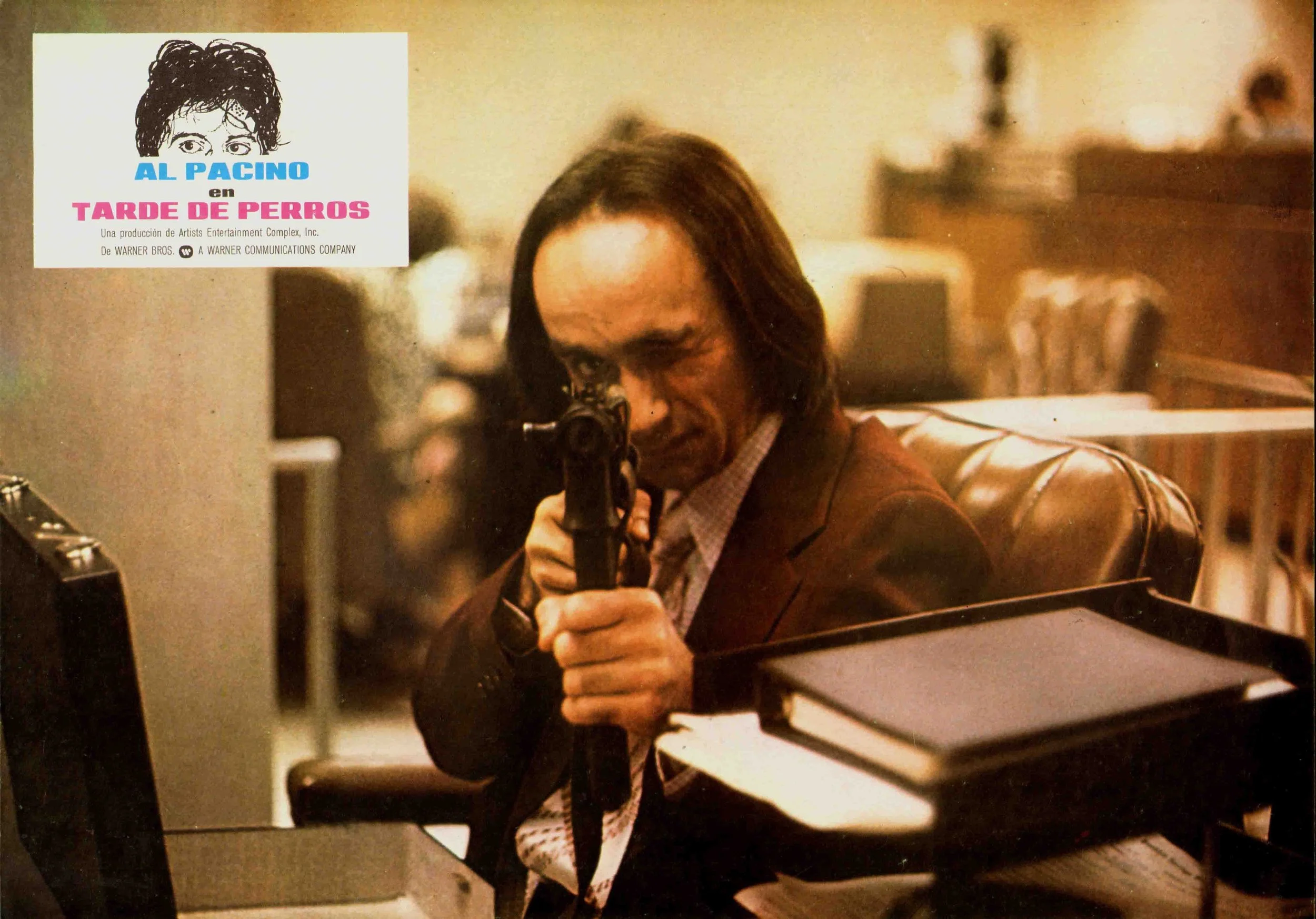

It is a hot and muggy late August afternoon and employees of the First Brooklyn Savings Bank are winding down for the day. The staff includes a bank manager, security guard, and a group of young-to-middle-aged women working as tellers. Enter would-be bank robbers Sonny Wortzik (Al Pacino) and his literal partner-in-crime Sal (John Cazale), the former brandishing a rifle and the latter a submachine gun. Sonny is a jittery, anxious, and financially strapped Vietnam veteran and the mastermind behind the robbery. He is also a gay man with an estranged wife, two young kids, and, unbeknownst to some, a same-sex partner named Leon (Chris Sarandon) whom he married in a private and secret ceremony. Leon is emotionally distraught, suicidal, and was recently institutionalized; he has also struggled to come out as a transgender woman. Adding to Leon’s stress is living with a volatile and catastrophizing Sonny who frequently utters, “I’m dying here!” Sonny’s primary impetus for the heist? To procure enough money (around $2,500) to pay for Leon’s gender reassignment surgery. Sal, about whom we know much less, is a quiet, awkward, and intense man who exudes an air of melancholy. He also seems to live by some kind of ethical code that we are not privy to.

The heist begins to go south almost immediately when the duo discovers that a tip they received was erroneous and that the money held in the vault was removed earlier in the day. This realization compels our amateurs to sift through the bank’s nooks and crannies to collect some cash. While not amassing the windfall they were expecting, Sonny & Sal pull together a modest score and are ready to skedaddle when they learn that the police have surrounded the bank. The two have no choice (aside from surrendering) but to make hostages of the bank employees and sort their way out of a scenario for which they clearly did not plan.

The Jig is Up

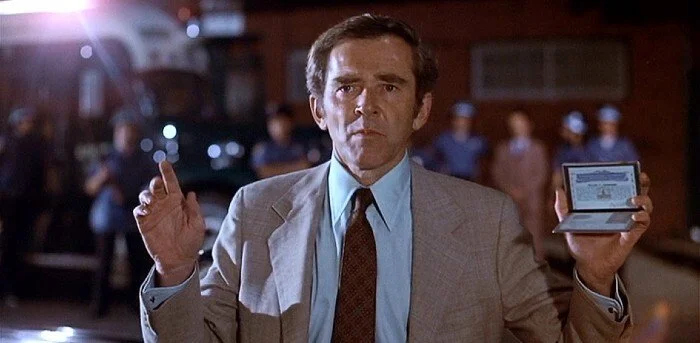

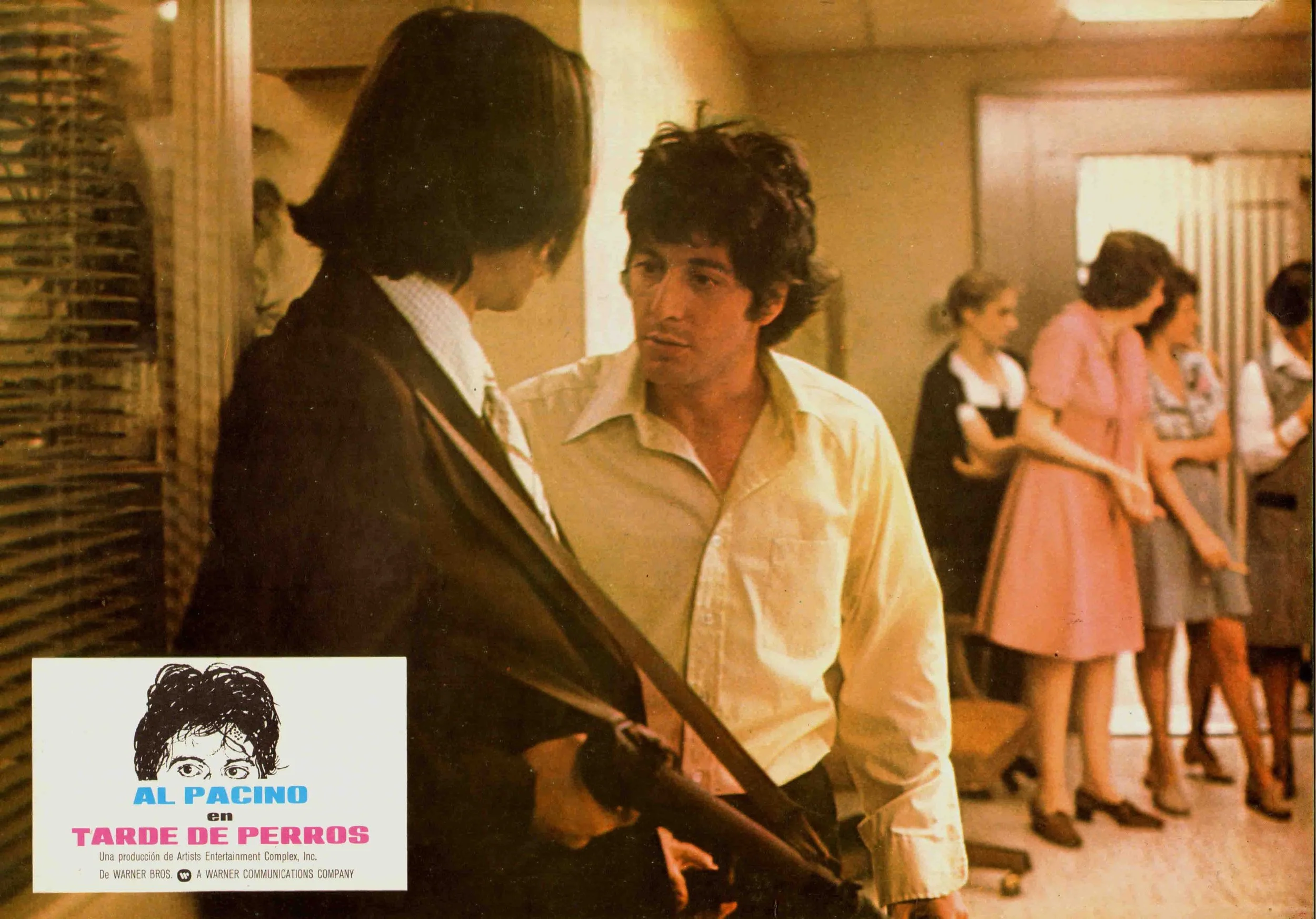

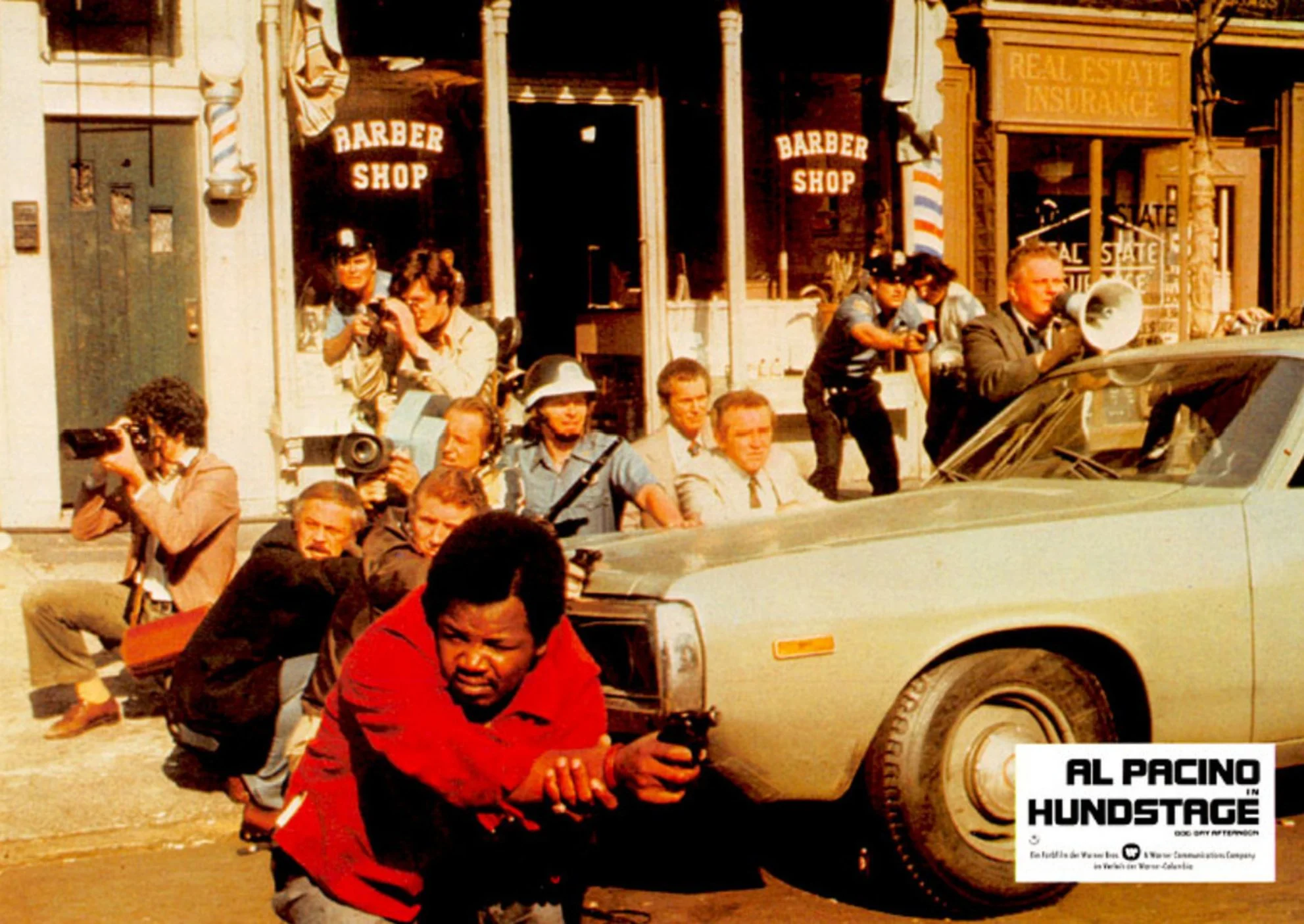

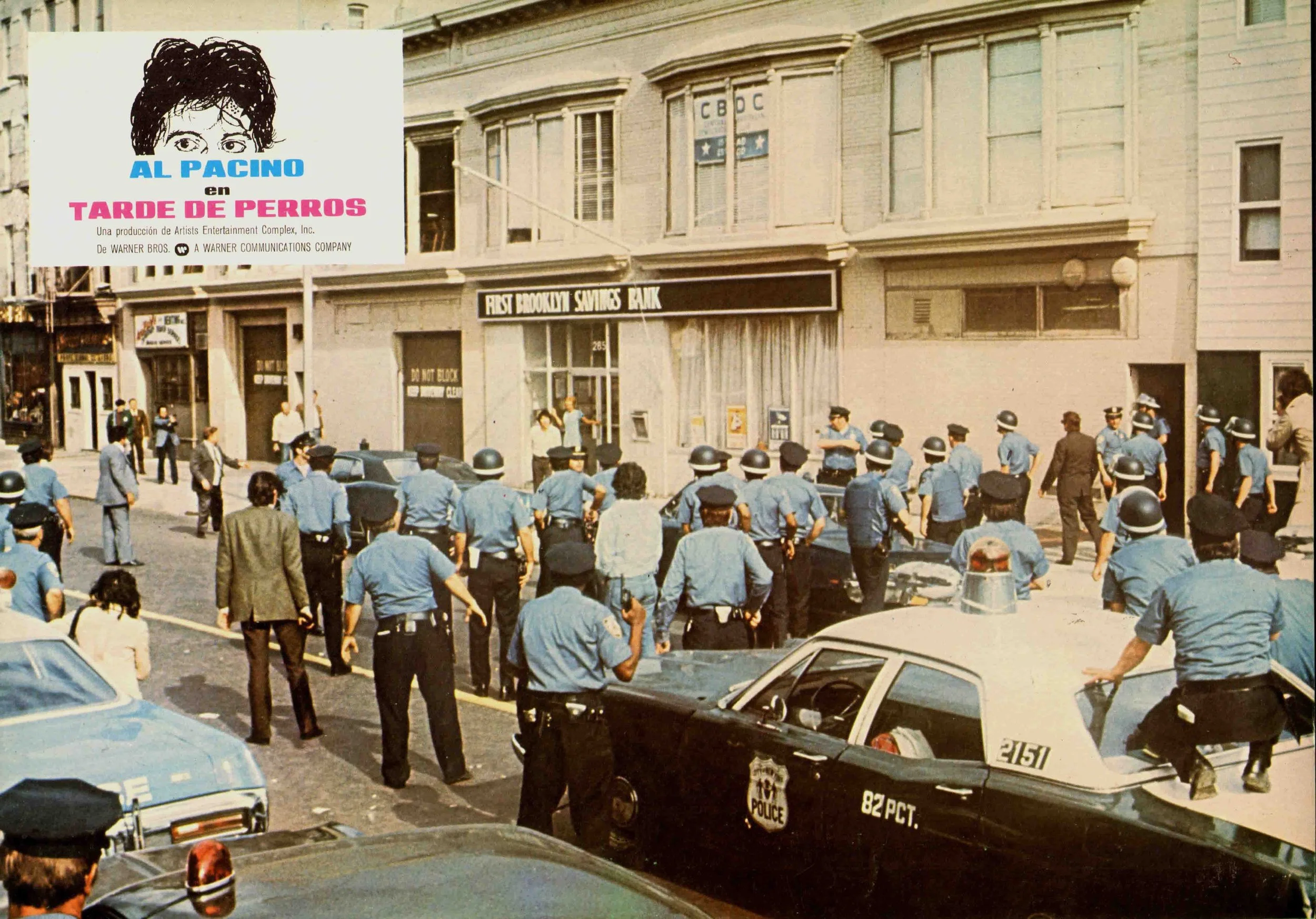

Sonny and Sal are quickly under siege as cops, detectives, and FBI agents block off the streets and set up a makeshift command center in a barber shop across the street. Meanwhile, helicopters buzz overhead, the local media begin reporting from the scene, and an enthusiastic and particularly boisterious crowd of spectators gathers just outside the barricades. In charge of negotiations and keeping the escalating media circus and gawking crowds at bay is New York police detective Sergeant Eugene Moretti (Charles Durning). Stressed yet doing his best to diffuse the situation, Moretti starts an intermittent dialogue with an increasingly weary yet wired Sonny.

Inside the bank, Sonny and Sal establish a rapport with the tellers who settle into their situation as hostages with resignation, humor, and even a bit of fun. There also seems to be a sense of mutual understanding between this pair of outcasts and cohort of working-class women. In fact, the question of labor and a living wage comes up several times between Sonny and the hostages—he even references it during an impromptu phone interview he gives to a reporter. Head teller Sylvia (Penelope Allen), no shrinking violet, banters and at times scolds Sonny for such a poorly planned bank robbery. At one point she is given an opportunity to leave with Moretti but she refuses, opting to stay with “her girls.” To further complicate matters, the bank manager Mr. Mulvaney suffers from a diabetic episode, creating yet one more wrinkle in a robbery gone terribly wrong.

“Attica, Attica!”

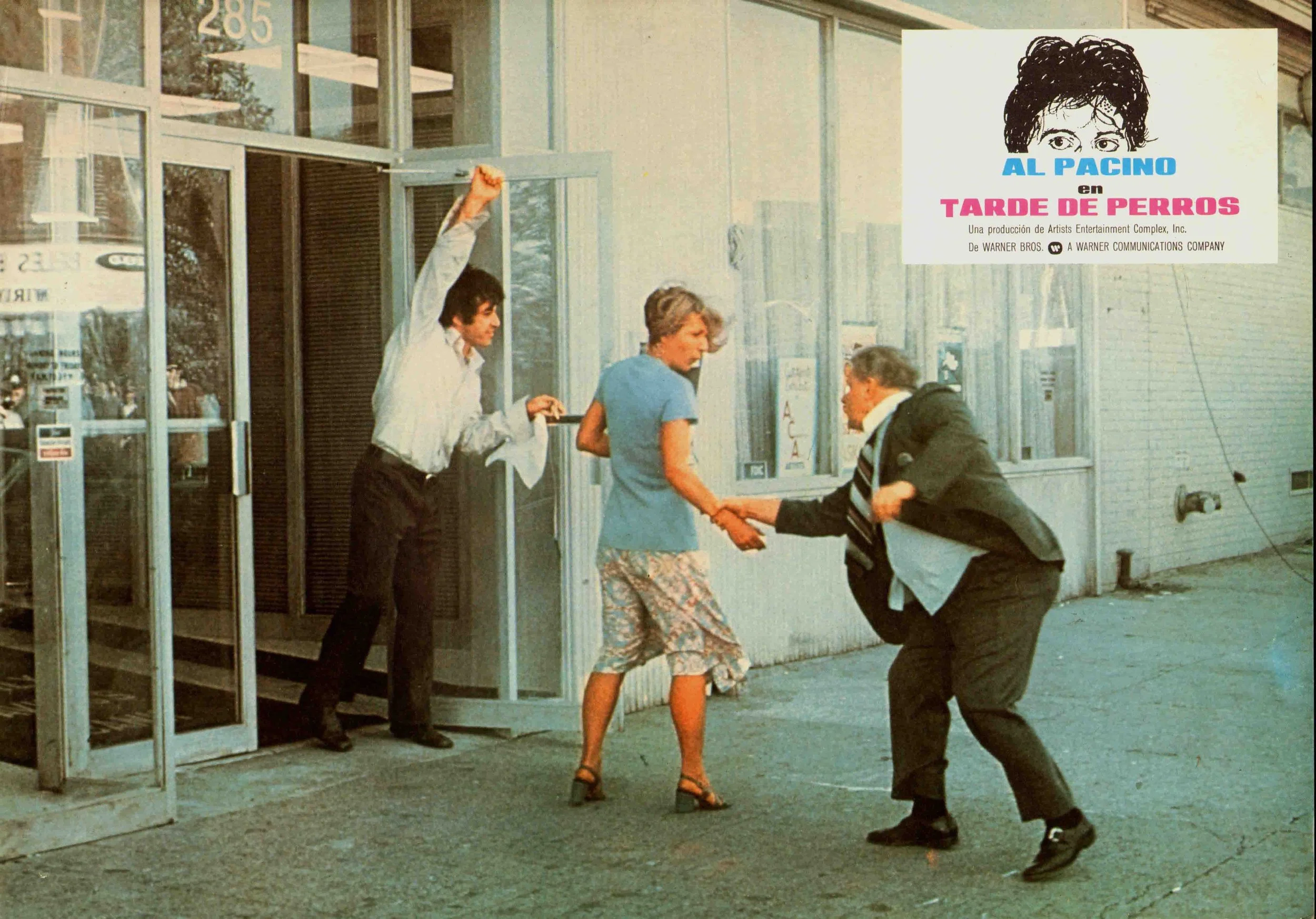

In a couple of now-iconic sequences, cops and detectives creep closer and closer to Sonny as he and Moretti talk just outside the bank doors. Sensing itchy trigger fingers and with recent history fresh in his mind, Sonny starts to push back with a spontaneous (and initially unscripted) chant:

Attica! Attica! Attica! Attica! Attica! Attica! Attica! Attica!

(Gesturing towards the crowd) Attica! Attica! Remember Attica!”

For those unaware, Sonny was referring to the Attica Correctional Facility in New York where in September 1971 prisoners staged an uprising and took hostages hoping to negotiate better treatment at the facility. After a tense four-day standoff New York State Police stormed the prison, ultimately killing 33 inmates and 10 correctional officers. It would become a symbol of police aggression and prison system failures and a rallying cry for resistance and reform.

Negotiations & Goodbyes

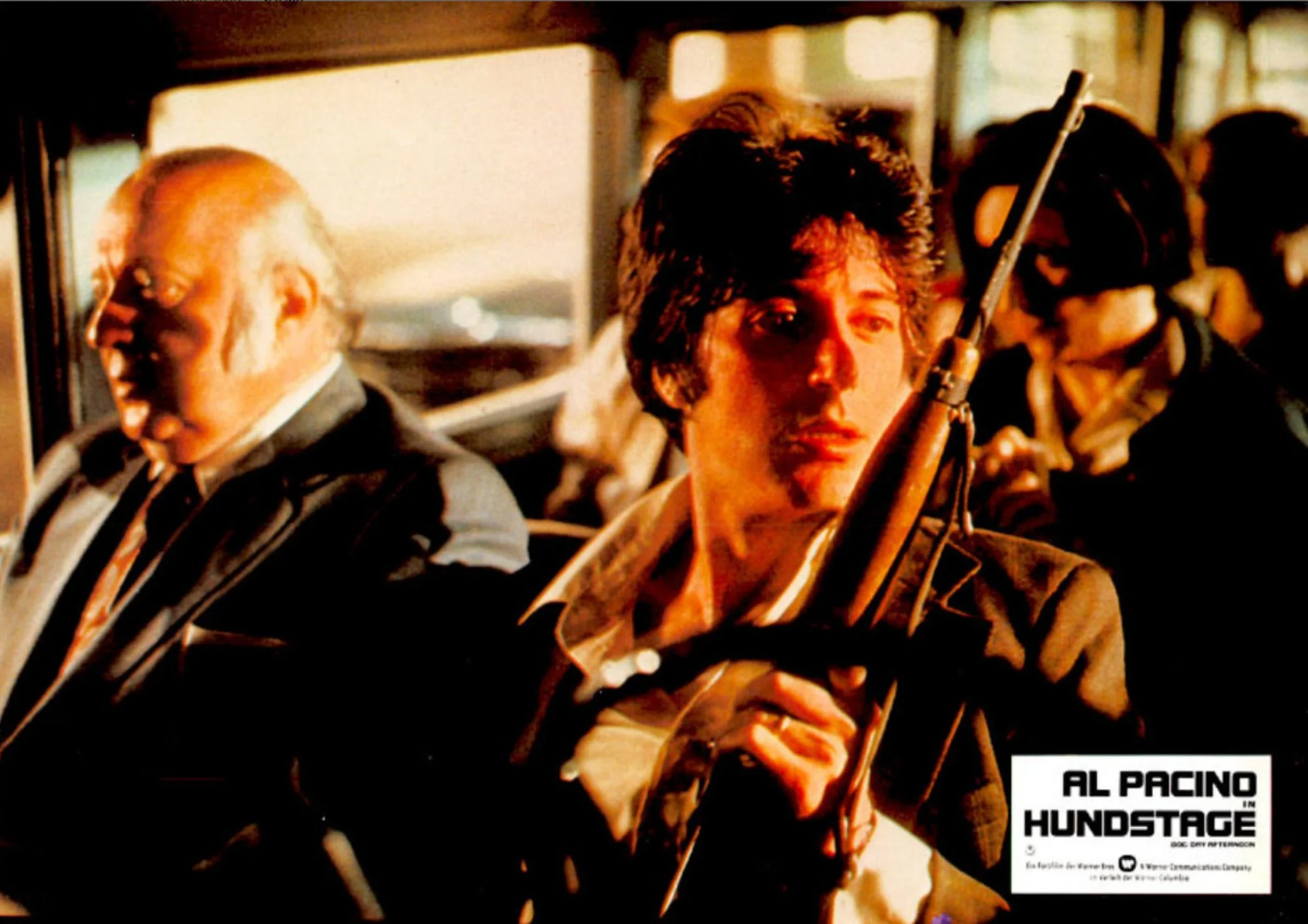

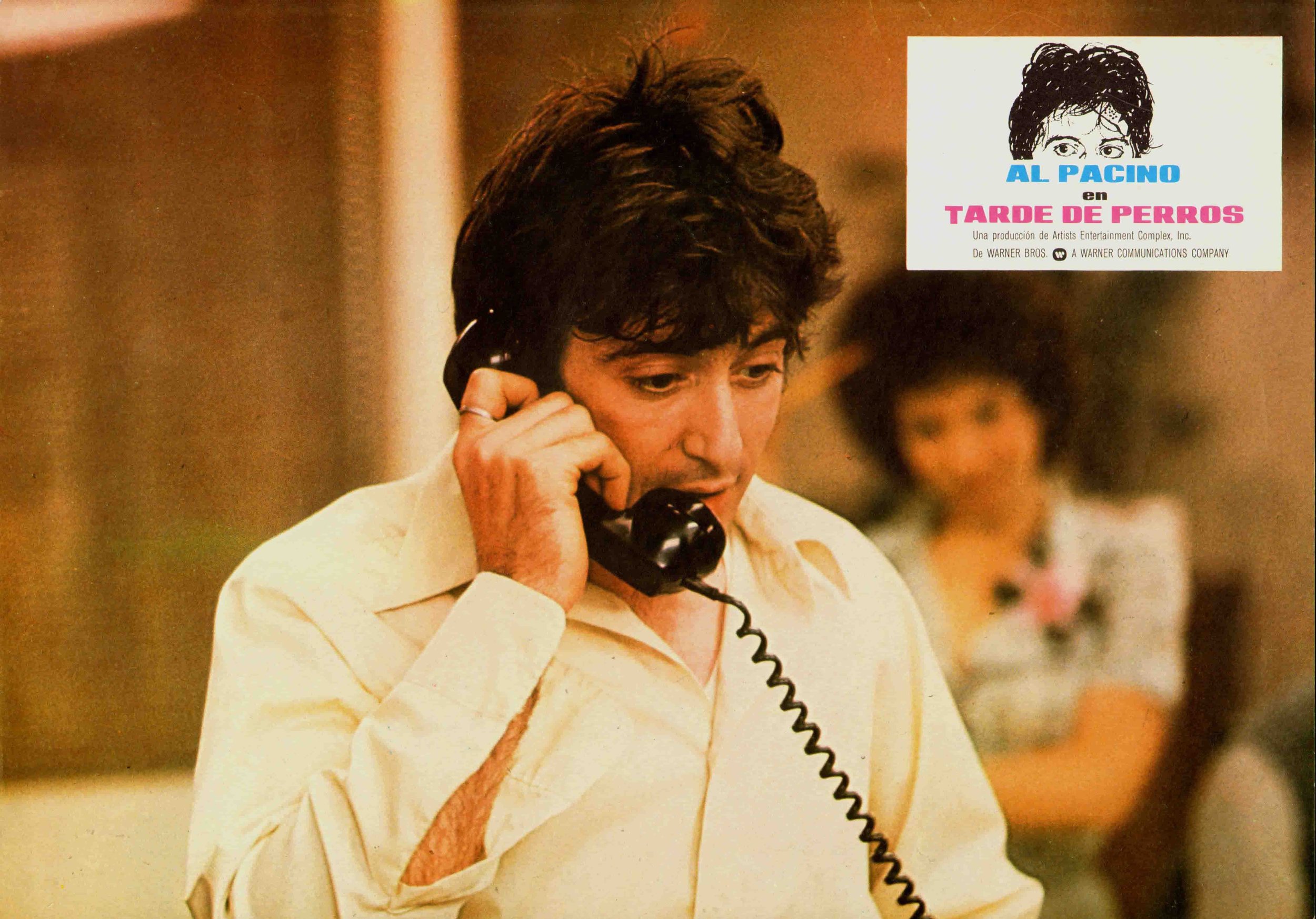

As the stalemate stretches on into the night it becomes clear that the FBI agents—who up to this point had been shadowing Moretti—have taken charge. Agents Sheldon (James Broderick) and Murphy (Lance Henrikson) have the power cut off to the bank, leaving Sonny, Sal, and the staff to literally sweat it out in the dark. A seemingly stoic Agent Sheldon, holding his cards tight to his chest, engages with Sonny in some final negotiations while sizing up the situation. The deal involves transportation, with hostages in tow, to JFK airport, where a jet will be ready to take Sonny and Sal to Algeria (a choice that is arbitrary at best).

Before departing, Sonny has a series of final goodbyes—with Leon and Angie by phone, and with his mom in person. I won’t spoil the substance of these conversations but suffice to say that they give us the closest glimpse at Sonny’s strained psyche and its impact on those in his sphere. These are poignant, revealing, and heartbreaking scenes that never veer into melodrama.

My two cents

I am hardly going out on a limb when I say that Dog Day Afternoon is an unqualified classic, with its place secure amongst the great NYC-based crime dramas and thrillers of the 1970s. It stands out for its semi-improvisational performances and Director Sidney Lumet’s natural, unaffected style of filmmaking that forgoes virtually any stylization. The movie is also engrossing as a historic snapshot of the anxieties and socioeconomic issues of the day. And while I am not qualified to say whether or not Sonny’s bit of bonding with the hostages represents a true case of Stockholm Syndrome, it does present a fascinating dynamic and has an air of authenticity thanks to the stellar cast.

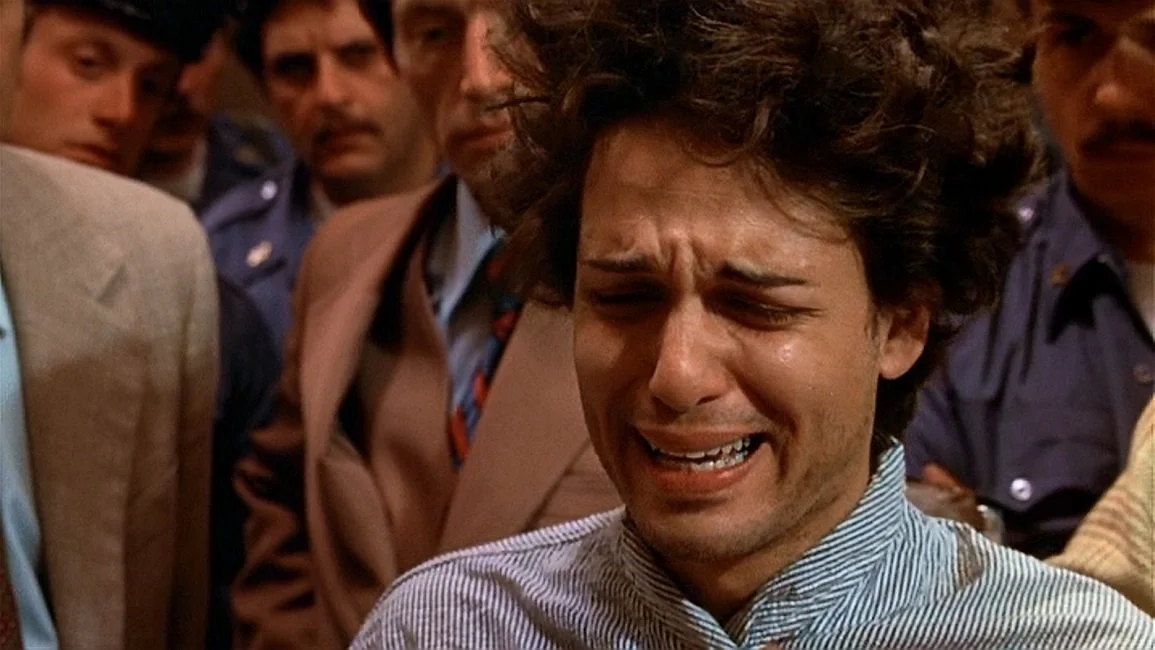

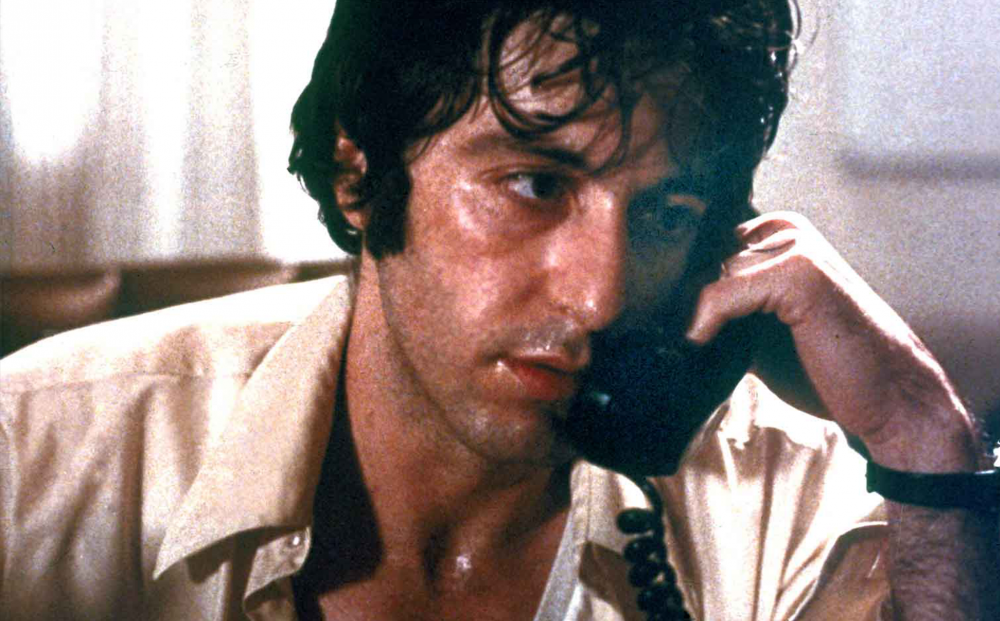

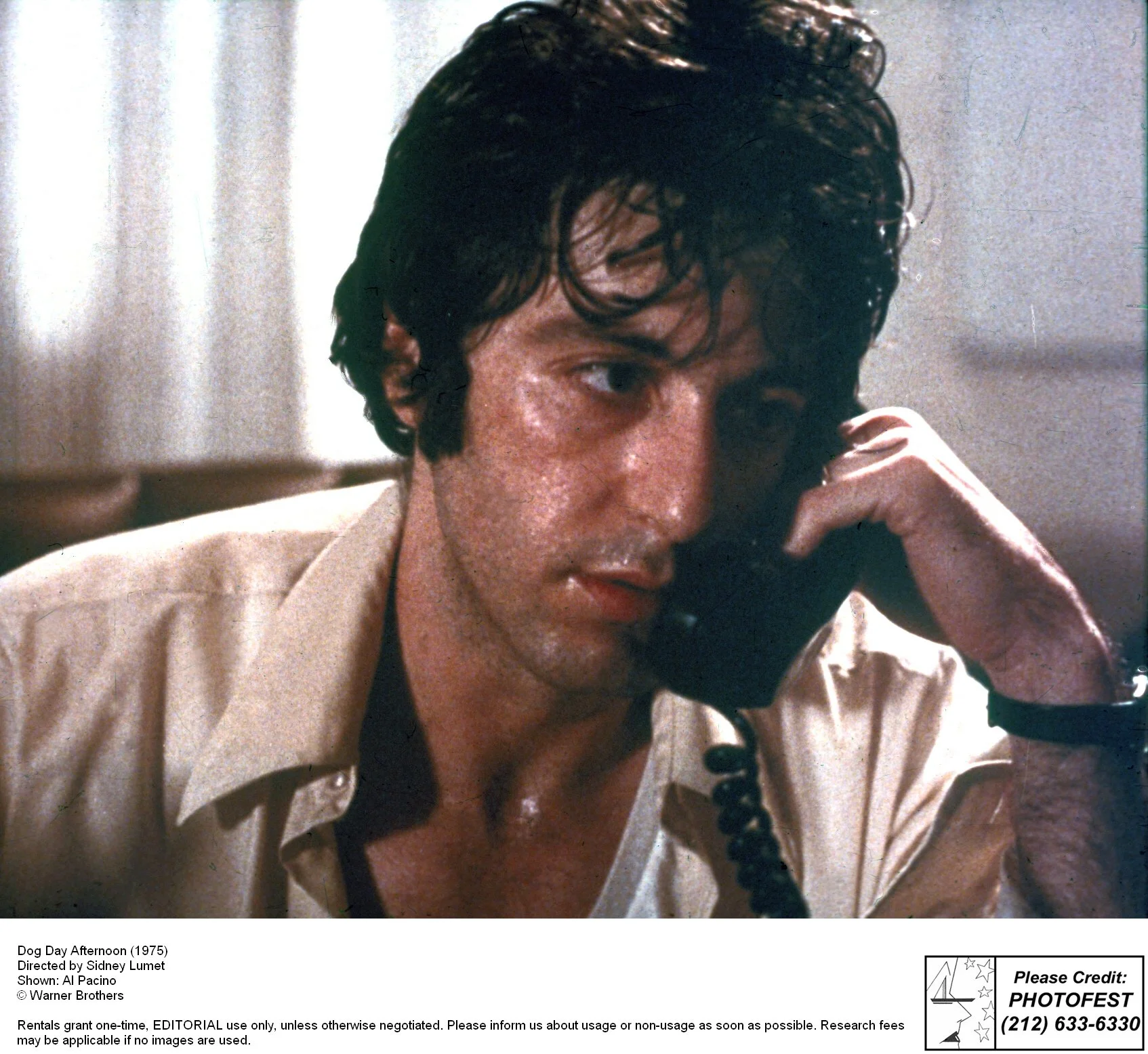

Al Pacino’s performances in the 1970s alone have been studied and celebrated for decades, and his role in this film is no exception. Pacino’s Sonny is wild-eyed, erratic, and dangerous and yet we find ourselves rooting for him. He is at once foolhardy, impractical, intelligent, and empathic as a bumbling antihero whose actions stem from deep financial instability and trauma. His is a riveting and raw performance that you simply cannot look away from. The brilliant John Cazale is moving as Sal, someone operating by equal parts conviction and confusion. No one plays understated and vulnerable characters like Cazale, who we last talked about as part of our Cinematic Semicentennial Series feature on The Conversation (1974).

Charles Durning, who shines in every role he plays, is a standout as Sergeant Moretti, a guy in a tough spot who acts in reasonably good faith and tries to keep everyone alive. Chris Sarandon is equally engrossing in a small yet consequential part as the disoriented Leon whose path to a fully realized gender identity takes a wild detour courtesy of Sonny. Penelope Allen makes her mark as the strong, cool-headed, and occasionally sassy Sylvia who is fiercely protective of her girls. We love her! One last shoutout to a young Carol Kane who adds to the charm and character of the bank’s female cohort.

The film, which was mostly shot on location around Brooklyn and a bit in Queens, took full advantage of natural light photography, camera-ready neighborhood locales, and hundreds of extras, many of them native Brooklynites.

As much as I am a film score guy, Dog Day Afternoon’s complete lack of music feels right, complementing Lumet’s unvarnished approach. The one musical exception is Elton John’s “Amoreena,” which plays over an opening montage that includes quite a few shots around New York City’s boroughs. It reveals a cross section of everyday life in New York: construction workers, the iconic Circle Line boat pulling out onto the Hudson, people at the local beaches and pools, commuters, unhoused people, toll booths, city parks, and folks simply lazing in the sweltering heat of summer. And while this unfiltered collage picks up a share of the grit, grime, and struggles of the city in the 1970s, it also reminds us that people went about the business of living even in difficult times.

As fraught and potentially dangerous as the events of Dog Day Afternoon are, moments of warmth and humor are found throughout the film. It is as if Lumet is saying that even in this often cold, chaotic, and cruel world you must eke out joy and perhaps a few laughs where you can.

As Sonny himself says,“You gotta get fun out of life.”

Dog Day Afternoon at 50

Dog Day Afternoon premiered in New York on September 21, 1975, and was both a critical and box office success bringing in more than $50 million at the domestic box office against a budget of nearly $4 million. It received seven nominations from the British Academy of Film and Television Arts, with Pacino winning for best actor and Dede Allen for Best Film editing. The film garnered six Academy Award nominations, with writer Frank Pierson winning the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay in 1976. In 2009, the movie was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress.

Without being the least bit heavy handed, Dog Day Afternoon is a cinematic collage of the many pressing issues of the era: economic recession and insecurity, the burgeoning post-Stonewall LGBTQ+ rights movement, pushback against police brutality, a zeitgeist that soured on symbols of authority, and a growing mistrust of institutions post-Watergate and the catastrophic and seemingly unending morass of the Vietnam war.

Lumet tackled social issues and stories of individuals grappling with corrupt systems and the limits of institutional justice in several of his films, including 12 Angry Men (1957), Serpico (1973), Prince of the City (1981), and The Verdict (1982). Some 20 odd years ago, I had the fortune of attending a 35mm screening of Serpico at the Museum of the Moving Image, followed by a discussion with Lumet. It was a pleasure listening to him talk about film in the most unpretentious way, heaping praise on Pacino and all the wonderful actors he had worked with over the years. Lumet passed away on April 9, 2011.

The legacy of Dog Day Afternoon lives on in many forms, most famously via the often quoted “Attica! Attica!” chant. It is right up there with Dustin Hoffman’s Ratzo Rizzo exclaiming “I’m walking here!” in Midnight Cowboy or Robert De Niro’s Travis Bickle in front of the mirror asking, “Are you Talking to me?”

Yassmeen and I watch this film almost every summer and we haven’t tired of it. In recent news, we found out that Dog Day Afternoon is coming to Broadway for a limited run at the August Wilson Theater and will star John Bernthal and Ebon Moss-Bachrach.

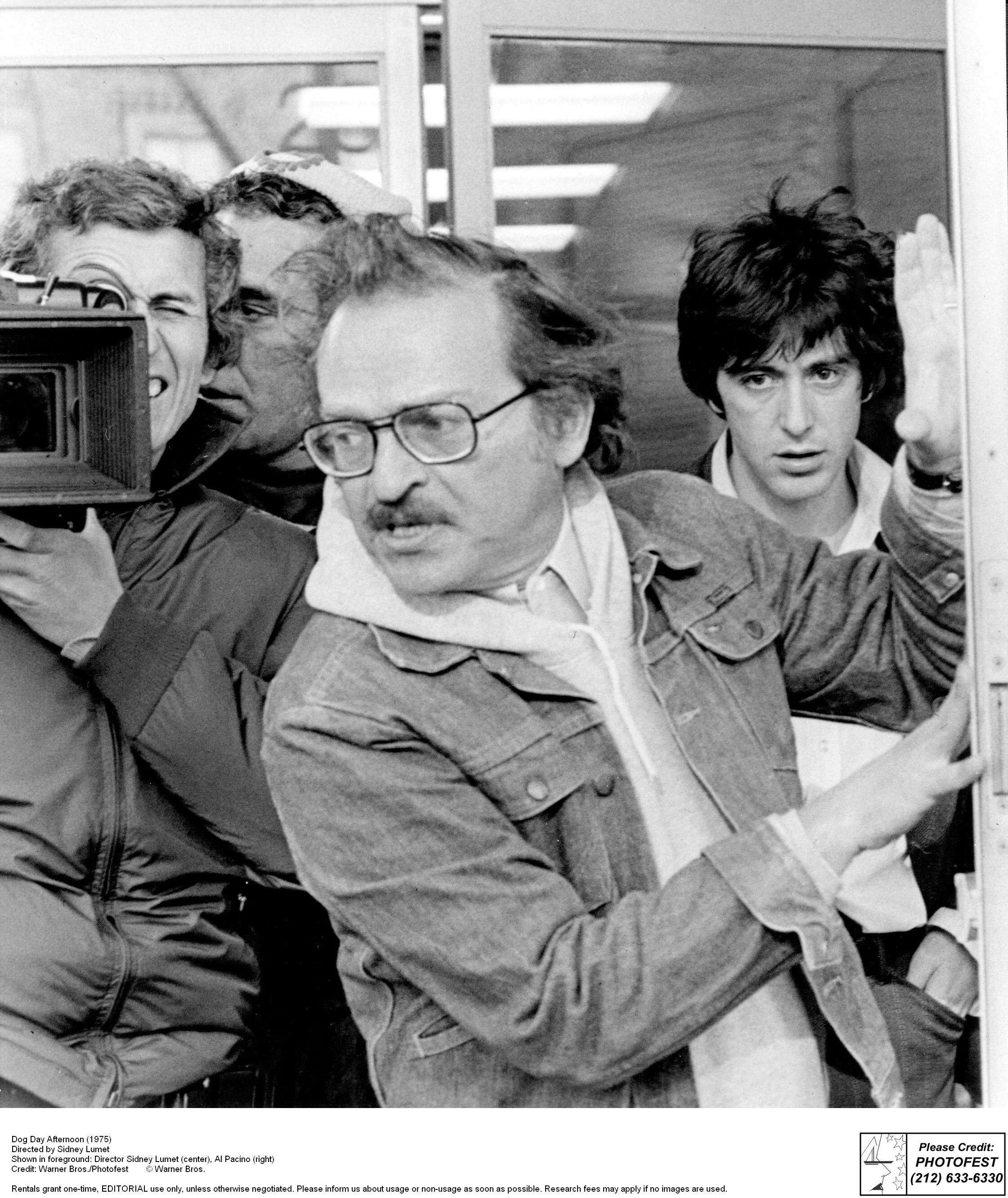

Behind-the-scenes photos of Lumet & Pacino during the filming of Dog Day Afternoon.

Cast (abridged)

Al Pacino – Sonny

John Cazale – Sal

Beulah Garrick – Margaret

Penelope Allen – Sylvia

Charles Durning – Moretti

Carol Kane – Jenny

James Broderick - FBI Agent Sheldon

Sandra Kazan – Deborah

Marcia Jean Kurtz – Miriam

Amy Levitt – Maria

John Marriott – Howard

Estelle Omens – Edna

Sully Boyar – Mulvaney

Lance Henriksen – Murphy

Crew (abridged)

Director – Sidney Lumet

Screenwriter – Frank Pierson

Cinematographer – Victor J. Kemper

Editor – Dede Allen

Production Designer – Charles Bailey

Art Direction – Doug Higgins

Producers – Martin Bregman, Martin Elfand

Production Company – Arts Entertainment Complex Production

How did I watch?

Warner Brothers 40th Anniversary Blu-ray

Running Time: 2h 5m

MPAA Rating: R

Did you know?

The real Sal (Naturile) was a young, handsome, and intense man in his late teens, which is why Lumet was reluctant to cast the 40-year-old John Cazale. However, Al Pacino recommended him to the role. Following Cazale’s audition, Lumet determined that he was just too good not to cast.

Chris Sarandon was proud of his portrayal of Leon, though acknowledged that if the movie was made today that it would be more appropriate for the part be played by an actual trans actor.

According to an IMDB trivia note, Pacino reportedly only slept a few hours per night, ate little, and subjected himself to cold showers all to capture Sonny's disheveled, exhausted, wired, and

frazzled look.

Ironically, Dog Day Afternoon, a film that captures a sweltering sweaty NYC summer so well, was filmed on some particularly chilly fall days. Actors purportedly held ice chips in their mouths to cool their breath before it hit the cold air during outdoor scenes.

Sonny and Sal had a third accomplice by the name of Stevie who loses his nerve and begs out at the beginning of the robbery. He is played by Gary Springer, an entertainment publicist who dabbled in some acting in his early career. You may recognize him as one of the teens who head out on an ill-fated sailing trip in Jaws 2 (1978).

James Broderick, who played FBI Agent Sheldon, is the father of actor Mathew Broderick. We last met Broderick Sr. in The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, where he played the motorman of a highjacked NYC subway train car. We featured this crackling subway caper as part of our Cinematic Semicentennial Series 1974 edition.

The extensive interior shots of the fictional First Brooklyn Savings Bank were filmed in a repurposed warehouse in Flatbush while the exterior shots outside the bank were filmed on Prospect Park West between 17th and 18th Streets.

Dustin Hoffman was also up for the role of Sonny; Pacino had waffled on taking the part in the wake of his demanding work on The Godfather Part II.

Large parts of the film’s dialogue were born out of improvisations during rehearsals and were weaved into the final Academy Award-winning screenplay from Frank Pierson.

Recommendations based on Dog Day Afternoon

Serpico (1973)

Meanstreets (1973)

The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974)

Taxi Driver (1976)

Supplements-

Al Pacino on Dog Day Afternoon at 50: ‘It Plays More Todays Than it Even Did Then,” (The Guardian)

The Heartrending Movies of John Cazale (The New Yorker)

Marking 50 years of 'Dog Day Afternoon' with director Sidney Lumet and star Al Pacino (NPR audio, plus transcript)

The Real Story of John Wojtowicz and The Bank Robbery That Inspired ‘Dog Day Afternoon’ (ATI)

Sidney Lumet on Dog Day Afternoon and actor John Cazale (Youtube)

We at Concentric Cinema wish you all a Happy and healthy New Year!